Industrialization Spreads, 1750 to 1900

The Industrial Revolution, which began in Great Britain in the late 18th century, was one of the most transformative events in human history. This shift from handcrafting goods to large-scale industrial manufacturing changed economies, societies, and cultures across the globe. As the benefits of industrialization became clear, countries outside Britain began to adopt and adapt industrial technologies, leading to its rapid spread between 1750 and 1900. This period marked a pivotal moment in global history, as nations competed to harness industrial advancements for economic and political power.

In this article, we will explore how “Industrialization Spreads, 1750 to 1900”, highlighting the key factors that drove this expansion, the regions that industrialized, and the broader impacts of industrialization on global economies.

Industrialization Beyond Great Britain

Great Britain’s industrial success did not go unnoticed. Countries in Europe, the Americas, and Asia observed how industrialization boosted Britain’s economy, increased production, and solidified its global dominance. Inspired by this, other nations began their own industrial revolutions, each adapting the process to suit their unique political, social, and economic conditions.

Key Reasons for Industrialization Spread:

Technological Diffusion: Innovations like the steam engine, power looms, and coal-powered machinery spread to other regions.

Economic Competition: Nations sought to compete with Britain’s dominance in manufacturing and trade.

Resource Availability: Access to coal, iron, and waterways facilitated industrialization.

Population Growth: Increasing populations provided cheap labor for factories.

Government Policies: Some states actively invested in infrastructure and industrial growth.

Below, we discuss how industrialization unfolded in major regions like Europe, the United States, Russia, and Japan.

Industrialization in Europe

After Britain, industrialization spread to Western Europe, particularly France, Germany, and Belgium. However, European industrialization was gradual due to wars and political instability.

France

France adopted industrialization after overcoming economic disruptions caused by the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars. The French government supported infrastructure projects like railways and invested in textile and steel industries to catch up with Britain. While France industrialized slower, it remained a significant player in the global economy by 1900.

Germany

Germany became a powerhouse in industrial production after unification in 1871. Under leaders like Otto von Bismarck, Germany developed advanced steel and coal industries, which fueled its rapid industrialization. By the late 19th century, Germany surpassed Britain in coal and steel output, solidifying itself as a global industrial leader. The nation’s emphasis on scientific research and education further accelerated its growth.

Belgium

Belgium was one of the first countries on the European mainland to industrialize, benefiting from its rich coal deposits and well-developed transport infrastructure. It became a hub for textile manufacturing, machinery, and coal production.

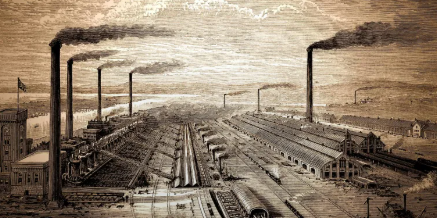

Industrialization in the United States

The United States emerged as a leading industrial power by the end of the 19th century. Several factors contributed to its rapid industrialization:

Population Growth and Immigration: Throughout the 1800s, millions of immigrants arrived in the United States, providing a vast labor pool for factories. Immigrants from Ireland, Germany, China, and later Southern and Eastern Europe settled in urban areas, fueling industrial growth.

Natural Resources: The U.S. had abundant natural resources, including coal, timber, iron, and oil.

Innovation and Infrastructure: The United States invested heavily in infrastructure, including railroads, canals, and telegraph systems, which connected factories to markets. The invention of assembly lines and mass production methods revolutionized manufacturing.

Government Policies: Policies protecting private property and patents encouraged investment and innovation.

By the late 19th century, cities like New York, Chicago, and Pittsburgh became centers of industry, producing steel, textiles, and machinery on an unprecedented scale.

Industrialization in Russia

Russia’s industrialization was unique because it was primarily state-driven rather than led by private enterprise. The Russian government actively invested in industrial projects to modernize its economy and maintain its position as a major world power.

Trans-Siberian Railroad

One of Russia’s most significant industrial achievements was the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railroad in the late 19th century. This massive infrastructure project connected the western cities of Russia with the remote eastern regions, promoting trade, resource extraction, and migration.

Focus on Heavy Industry

Russia emphasized heavy industry, particularly coal, iron, and steel production. While industrialization advanced in cities like Moscow and St. Petersburg, much of Russia’s economy remained agrarian, with a large population of peasants tied to subsistence farming.

The combination of industrialization and poor working conditions eventually contributed to growing dissatisfaction, setting the stage for revolutionary movements in the 20th century.

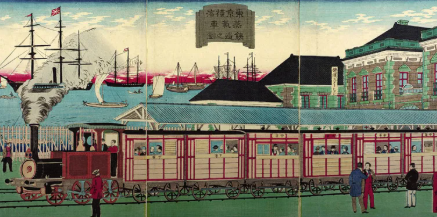

Industrialization in Japan

Japan’s industrialization was remarkable for its speed and purpose. Unlike Western nations, Japan industrialized primarily to defend its sovereignty and avoid becoming a victim of Western imperialism.

Meiji Restoration

The Meiji Restoration (1868) marked the beginning of Japan’s industrial revolution. The Japanese government actively promoted modernization by:

Sending scholars to study Western technologies and systems.

Investing in railways, factories, and shipyards.

Encouraging private enterprise through government support.

Role of Education

Japan’s highly literate and educated population played a key role in its rapid industrialization. Skilled workers and engineers quickly adopted and improved upon Western technologies.

By the late 19th century, Japan emerged as an industrial and military power in Asia, successfully competing with Western nations.

Industrial Production and Global Disparities

The spread of industrialization created stark differences in global manufacturing output. Steam-powered factories in Europe, the United States, and Japan produced goods on an enormous scale, dominating global trade. Meanwhile, traditional manufacturing in Asia and the Middle East declined in relative significance.

Regions Impacted by Industrial Decline

India: India, under British colonial rule, saw its traditional industries, like textile production, decline as cheap, machine-made textiles from Britain flooded the market. Iron production also suffered due to British competition.

Egypt: Egypt’s textile industry weakened as industrialized European goods displaced locally-made products.

Southeast Asia: Shipbuilding industries in regions like Indonesia and the Philippines declined due to European control over maritime trade.

These regions continued to produce goods, but without industrial technology, they could not match the output of steam-powered factories.

Impact of Industrialization Spread

The spread of industrialization between 1750 and 1900 had far-reaching effects on the global economy, societies, and the environment:

1. Economic Impact

Increased Production: Industrialized nations produced goods faster, cheaper, and on a massive scale.

Global Trade: New transportation technologies like steamships and railroads connected markets worldwide, leading to a surge in global trade.

Shift in Wealth: Europe, the United States, and Japan grew economically dominant, while non-industrialized regions experienced economic stagnation.

2. Social Impact

Urbanization: The rise of factories led to the rapid growth of cities, with large populations migrating for work.

Labor Movements: Poor working conditions and low wages gave rise to labor unions and workers’ rights movements.

Changing Class Structures: A new middle class of factory owners, managers, and professionals emerged, while the working class expanded significantly.

3. Environmental Impact

Resource Exploitation: Industrialization increased the demand for coal, timber, and other natural resources, leading to deforestation and environmental degradation.

Pollution: Factory emissions and waste contributed to severe air and water pollution in industrial cities.

Conclusion: Industrialization Spreads, 1750 to 1900

The period from 1750 to 1900 marked the global spread of industrialization, transforming economies, societies, and political systems. Beginning in Great Britain, industrialization spread to Europe, the United States, Russia, and Japan, each region adapting it to their own unique contexts. This spread created a significant economic divide between industrialized and non-industrialized regions, altering global power dynamics.

Nations that embraced industrialization became economic leaders, while others, like India and Egypt, experienced industrial decline due to colonial exploitation. The advancements of the Industrial Revolution laid the foundation for the modern industrialized world, shaping the economic and social landscapes we recognize today.

As we reflect on how “Industrialization Spreads, 1750 to 1900”, it becomes clear that this era marked a turning point in human history—a shift toward modernity, innovation, and global interconnectedness.

Key Takeaways

Industrialization began in Britain and spread to Europe, the United States, Russia, and Japan.

Government policies, access to resources, and population growth played key roles in industrialization.

Steam power and fossil fuels revolutionized production and global trade.

Industrialized nations dominated the global economy, while traditional manufacturing regions declined.

By understanding this transformative era, we can better appreciate the complex forces that shaped our modern world.

FAQs on “Industrialization Spreads, 1750 to 1900” with Detailed Answers

1. What is the spread of industrialization?

The spread of industrialization refers to the global movement of industrial advancements from Britain to other parts of Europe, North America, and later Asia, between 1750 and 1900.

2. How did industrialization spread beyond Britain?

Industrialization spread through the sharing of technology, skilled labor migration, trade networks, and the influence of economic and political systems that encouraged industrial growth.

3. What factors allowed Britain to industrialize first?

Britain’s natural resources, stable government, colonial markets, strong banking system, and innovative culture were key factors that allowed it to lead industrialization.

4. Which European countries industrialized after Britain?

Countries like Belgium, France, Germany, and the Netherlands industrialized after Britain, with Germany and Belgium becoming significant industrial powers.

5. When did the United States begin industrializing?

The United States began industrializing in the early 19th century, particularly after 1815, with the growth of textile manufacturing, railroads, and steel production.

6. What role did canals and railroads play in spreading industrialization?

Canals and railroads facilitated the movement of raw materials, goods, and people, connecting rural and urban markets and accelerating industrial development.

7. How did the textile industry drive industrialization globally?

The mechanization of textile production spread from Britain to other countries, increasing demand for cotton and labor while transforming economies and trade patterns.

8. Why was Belgium the first industrialized nation in continental Europe?

Belgium had abundant coal and iron, a well-developed transportation network, and a strong textile industry, which enabled it to industrialize quickly.

9. How did industrialization spread to Germany?

Germany industrialized through investments in coal, iron, and railways, as well as a unified economic market created by the Zollverein customs union.

10. What were the impacts of industrialization on the United States?

Industrialization transformed the U.S. economy, leading to urbanization, the expansion of factories, technological innovations, and the rise of industrial cities like New York and Chicago.

11. What industries drove industrialization in the United States?

Industries such as textiles, railroads, steel, and oil drove industrialization, with leaders like Andrew Carnegie and John D. Rockefeller leading these sectors.

12. How did Japan industrialize during the Meiji Restoration?

Japan industrialized rapidly after 1868 by adopting Western technologies, building factories, modernizing infrastructure, and creating a strong centralized government.

13. What role did the steam engine play in spreading industrialization?

The steam engine powered factories, railways, and ships, enabling faster production and transportation, which helped spread industrialization globally.

14. What was the significance of railroads in industrialized nations?

Railroads connected urban centers to rural areas, reduced transportation costs, and facilitated the movement of goods, resources, and people.

15. How did industrialization impact Russia in the late 19th century?

Russia industrialized later than Western Europe, focusing on railways (e.g., Trans-Siberian Railway) and heavy industries like coal, iron, and steel.

16. What resources were most important for industrialization?

Key resources included coal, iron, cotton, oil, and later, steel. These materials fueled factories, railways, and technological advancements.

17. How did industrialization affect urbanization?

Industrialization led to the growth of cities as people migrated for factory jobs, resulting in rapid urbanization and overcrowded living conditions.

18. How did the United States become a global industrial leader?

The U.S. utilized abundant natural resources, a growing population, a strong railroad network, and technological innovations to dominate industrial production by 1900.

19. What were the social effects of industrialization?

Industrialization created new social classes (industrial middle class and working class), widened income gaps, and led to poor working and living conditions for many.

20. What was the impact of industrialization on global trade?

Industrialization increased global trade as countries exported manufactured goods and imported raw materials from colonies and other regions.

21. How did industrialization spread to France?

France industrialized slower due to political instability but focused on textiles, railways, and luxury goods, especially in urban centers like Paris.

22. What was the role of colonialism in spreading industrialization?

Colonialism provided raw materials (e.g., cotton, rubber) and new markets for industrialized nations, fueling further economic growth.

23. What were the environmental impacts of industrialization?

Industrialization caused pollution, deforestation, and resource depletion due to factory emissions, mining, and rapid urban growth.

24. How did industrialization transform agriculture?

New machines like the mechanical reaper and seed drill increased agricultural efficiency, allowing fewer farmers to produce more food.

25. What role did technological innovations play in spreading industrialization?

Innovations such as the steam engine, spinning jenny, Bessemer steel process, and electric power revolutionized production, transportation, and communication.

26. What was the impact of industrialization on women?

Women entered the workforce in textile mills and factories but were often paid less than men and worked under harsh conditions.

27. How did industrialization spread to Eastern Europe?

Eastern Europe industrialized slowly due to serfdom, lack of infrastructure, and political instability, but regions like Russia invested heavily in railways and heavy industry.

28. What was the significance of the Second Industrial Revolution (late 1800s)?

The Second Industrial Revolution focused on steel, electricity, chemicals, and telecommunication, leading to rapid industrial growth and technological advancements.

29. How did industrialization impact labor movements?

Industrialization led to the rise of labor unions and worker protests, advocating for better wages, working conditions, and shorter hours.

30. How did the factory system change production methods?

The factory system centralized production, replacing cottage industries and manual labor with machine-based mass production.

31. How did industrialization in Germany impact global power dynamics?

Germany’s rapid industrialization strengthened its economy and military, making it a major global power by the late 19th century.

32. How did industrialization impact education systems?

Industrialized nations expanded education to produce skilled workers, scientists, and engineers needed for factories and innovation.

33. How did industrialization spread to Italy?

Italy’s industrialization was concentrated in the north, with textile manufacturing, steel production, and infrastructure projects leading the way.

34. What industries developed during the Second Industrial Revolution?

Industries such as steel, chemicals, petroleum, electricity, and telecommunications drove the Second Industrial Revolution.

35. How did the invention of electricity accelerate industrialization?

Electricity provided a clean, efficient power source for factories, transportation, and lighting, increasing productivity and enabling new inventions.

36. What role did immigration play in U.S. industrialization?

Immigrants provided a large, cheap labor force for factories, railroads, and mines, fueling rapid industrial growth in the U.S.

37. How did industrialization affect global inequality?

Industrialized nations became wealthier and more powerful, while non-industrialized regions were exploited for resources and labor.

38. How did industrialization affect traditional craft industries?

Traditional craft industries declined as factory-produced goods became cheaper and more widely available.

39. What were the economic effects of industrialization?

Industrialization increased productivity, economic growth, and wealth, but it also widened the gap between the rich and poor.

40. How did industrialization impact Asia?

Japan industrialized rapidly during the Meiji Restoration, while China and India experienced slower industrial growth due to colonial influence.

41. What role did inventions like the telegraph play in industrialization?

The telegraph revolutionized communication, enabling faster decision-making and coordination for businesses and governments.

42. How did industrialization influence public health?

Industrial cities suffered from pollution and poor sanitation, but later reforms improved healthcare, sewage systems, and clean water access.

43. What impact did industrialization have on class structures?

A new industrial middle class (bourgeoisie) emerged, while the working class (proletariat) grew in size but faced harsh conditions.

44. What were the major transportation innovations during industrialization?

Key innovations included railways, steamships, and canals, which improved the movement of goods and people.

45. What role did nationalism play in industrialization?

Nationalism motivated governments to industrialize to strengthen their economies and compete with industrialized rivals.

46. How did industrialization impact the global economy?

It integrated economies through increased trade, new markets, and the exchange of goods, fueling globalization.

47. What were the major environmental challenges caused by industrialization?

Air pollution, deforestation, water contamination, and the overuse of natural resources were major challenges of industrial growth.

48. How did industrialization contribute to imperialism?

Industrialized nations sought colonies for raw materials, markets, and cheap labor, leading to imperial expansion.

49. How did labor unions develop during industrialization?

Workers formed labor unions to advocate for better wages, hours, and working conditions through strikes and collective bargaining.

50. What are the lasting impacts of industrialization between 1750-1900?

Industrialization transformed economies, societies, and global power structures, paving the way for modern technology, urbanization, and globalization.

r sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.