Unit 3: Work-Energy Theorem

Overview

Energy lies at the heart of physics, influencing nearly every concept we’ve covered so far and the ones we will explore in future lessons. The work-energy theorem connects the dots between force, motion, and energy, making it an essential tool for problem-solving in mechanics. Whether you’re calculating the speed of a car or determining how much effort it takes to lift a box, energy principles are always at play. A key takeaway? Nearly every AP Physics FRQ can incorporate energy concepts in some form!

Big Ideas

Force Interactions:

Why is no work done when you push against a wall, but work is done when you coast downhill?

Conservation:

Why does a stretched rubber band return to its original length?

Why is it easier to walk up a flight of steps rather than run, even when the gravitational potential energy remains the same?

Energy in Systems:

How do energy transfers occur within closed and open systems?

Exam Impact

Unit 3 constitutes 14%-17% of the AP Physics C: Mechanics exam. Expect to spend approximately 10-20 class periods (45 minutes each) on mastering this content. The AP Classroom Personal Progress Check includes 20 multiple-choice questions and 1 free-response question to solidify your understanding.

The Work-Energy Theorem

Definition: The work-energy theorem states that the net work done on an object is equal to its change in kinetic energy.

Formula: Where:

: Net work done on the object

: Change in kinetic energy

This principle underpins a wide range of physics problems, from analyzing the motion of a speeding car to understanding the behavior of objects in free fall.

Breaking Down Work and Energy

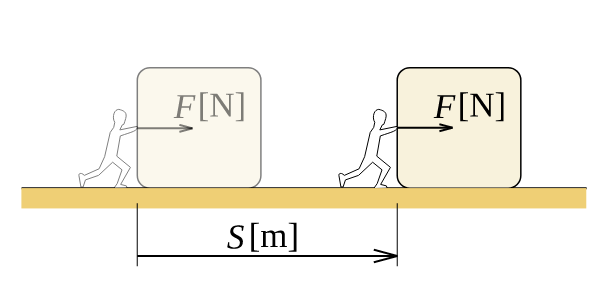

Work (“W”): Work occurs when a force applied to an object causes displacement. It is a scalar quantity, meaning it has magnitude but no direction.

Formula: Where:

: Force applied

: Displacement

: Angle between force and displacement vectors

Key Notes:

Positive work adds energy to a system.

Negative work removes energy from a system.

No work is done if there’s no displacement or the force is perpendicular to displacement (e.g., holding a bag without moving).

Kinetic Energy (“KE”): Energy possessed by an object due to its motion.

Formula: Where:

: Mass

: Velocity

Work-Energy Relationship: When work is performed on an object, it changes its kinetic energy.

Example: A car accelerating from rest experiences an increase in kinetic energy due to the work done by its engine.

Deriving the Work-Energy Theorem

Let’s derive the theorem step-by-step:

Force-Acceleration Relation:

Substitute Acceleration: Using , substitute:

Chain Rule for Velocity: Recognizing that :

Integrate to Find Work:

Result: Thus:

Graphical Interpretation

When analyzing force vs. displacement graphs:

The area under the curve represents the work done.

Real-World Applications

Accelerating Vehicles: The work-energy theorem explains why heavier vehicles require more force (or energy) to accelerate.

Sports: In pole vaulting, athletes convert kinetic energy into gravitational potential energy.

Engineering: Understanding energy efficiency in machines, such as cranes and elevators.

Practice Problems

Problem 1: Elevator Work

(a) Calculate the work done on a 1500-kg elevator car by its cable to lift it 40 m at a constant speed. Assume friction averages 100 N.

(b) What is the work done by gravity on the elevator during this process?

(c) What is the total work done on the elevator?

Solutions: (a) The tension force () must counteract gravity () and friction:

(b) Work done by gravity:

(c) Net work:

Problem 2: Sprinter’s Push

Using energy considerations, calculate the average force a 60-kg sprinter exerts on the track to accelerate from 2 m/s to 8 m/s over a distance of 25 m. Assume a headwind exerts 30 N against the sprinter.

Solution: Using : Total force includes overcoming air resistance:

Tips for Mastery

Understand Directionality: Positive work adds energy; negative work removes it.

Visualize Graphs: Use force vs. displacement graphs to interpret work.

Practice Free-Body Diagrams: Identify forces acting on the object.

Integrate Calculus: When forces are variable, integrate force with respect to displacement.

Conclusion

The work-energy theorem provides a powerful framework for analyzing motion and energy. By mastering this concept, you’ll unlock the ability to tackle a wide array of physics problems, from real-world engineering challenges to AP exam questions. Remember, energy concepts permeate nearly every facet of physics—so keep practicing and applying what you’ve learned!

Work-Energy Theorem FAQs

1. What is the Work-Energy Theorem?

The Work-Energy Theorem states that the net work done on an object is equal to the change in its kinetic energy. Mathematically: where is the total work done by all forces, and is the change in kinetic energy.

2. What is the formula for the Work-Energy Theorem?

The formula is: where:

is the mass of the object,

is the final velocity,

is the initial velocity.

3. How does the Work-Energy Theorem relate to Newton’s Second Law?

The theorem derives from Newton’s Second Law, , combined with the kinematic equation , linking force, motion, and energy.

4. What is kinetic energy?

Kinetic energy is the energy an object possesses due to its motion, given by:

5. How is work related to kinetic energy?

Work done by the net force changes the kinetic energy of an object. Positive work increases kinetic energy, while negative work decreases it.

6. What is the significance of the Work-Energy Theorem?

The theorem simplifies motion analysis by linking force and displacement to energy changes, eliminating the need to calculate acceleration or time explicitly.

7. Can the Work-Energy Theorem be applied to rotational motion?

Yes, the theorem applies to rotational motion. For rotational systems: where , is the moment of inertia, and is angular velocity.

8. How does the Work-Energy Theorem apply to free fall?

In free fall, the work done by gravity increases the kinetic energy of the object, converting potential energy into kinetic energy.

9. What is net work?

Net work is the total work done by all forces acting on an object. It accounts for both positive and negative contributions.

10. How does friction affect the Work-Energy Theorem?

Friction does negative work, reducing the net work and thus decreasing the kinetic energy of the object.

11. Can the Work-Energy Theorem be applied to non-conservative forces?

Yes, the theorem accounts for non-conservative forces like friction, as it considers the total work done by all forces.

12. What are conservative forces in the Work-Energy Theorem?

Conservative forces, such as gravity or spring forces, have work that depends only on the initial and final positions, not the path taken.

13. How does the Work-Energy Theorem explain projectile motion?

In projectile motion, the net work done by forces like gravity alters the kinetic energy, with gravitational potential energy converting to and from kinetic energy.

14. What is the difference between work and energy?

Work: Energy transfer due to force applied over a distance.

Energy: The capacity to do work.

15. How is the Work-Energy Theorem used in engineering?

The theorem is used to design systems where force and energy efficiency are crucial, such as roller coasters, engines, and braking systems.

16. What is the relationship between work and displacement?

Work is the product of force and displacement in the direction of the force:

17. Can the Work-Energy Theorem be applied to curved paths?

Yes, by summing the infinitesimal work contributions along the path, the theorem applies to curved motion.

18. How does the Work-Energy Theorem simplify calculations?

The theorem avoids direct calculation of acceleration or time by focusing on initial and final kinetic energy and net work.

19. What is the role of power in the Work-Energy Theorem?

Power is the rate of doing work. The theorem focuses on total work, while power measures how quickly work is done:

20. How is the Work-Energy Theorem applied in braking?

In braking, the work done by friction reduces the kinetic energy of the vehicle, bringing it to rest.

21. How does the Work-Energy Theorem apply to springs?

In spring systems, the work done compressing or stretching the spring changes its potential energy, which can then convert to kinetic energy.

22. What is work done by gravity?

Work done by gravity is: when an object moves vertically, altering its potential energy.

23. Can the Work-Energy Theorem explain collisions?

Yes, it explains energy changes during collisions, including elastic (kinetic energy conserved) and inelastic (kinetic energy partially lost) collisions.

24. How does air resistance affect the theorem?

Air resistance does negative work, reducing the net work and decreasing the kinetic energy of the object.

25. What is work done by a variable force?

For a variable force, work is calculated as: where is the force as a function of position.

26. How does the Work-Energy Theorem relate to potential energy?

Work done by conservative forces changes potential energy, which then affects the object’s kinetic energy.

27. How is the theorem applied to circular motion?

In uniform circular motion, no net work is done since kinetic energy remains constant. In non-uniform circular motion, net work changes the kinetic energy.

28. What is the role of torque in rotational work-energy?

In rotational systems: where is torque and is angular displacement.

29. How does the theorem apply to inclined planes?

On an inclined plane, work done against gravity changes potential energy, which may convert to kinetic energy as the object moves.

30. What is the efficiency of energy transfer?

Efficiency measures how effectively work converts to desired energy forms. It is calculated as:

31. How is work calculated in non-conservative systems?

Work in non-conservative systems includes contributions from dissipative forces like friction, altering the total mechanical energy.

32. How does the Work-Energy Theorem explain lifting objects?

When lifting objects, work done against gravity increases their gravitational potential energy, reflecting a change in energy state.

33. What is the connection between force and kinetic energy?

Force applied over a distance changes an object’s velocity, altering its kinetic energy as described by the theorem.

34. How does the theorem apply to pendulums?

In pendulums, energy alternates between kinetic and potential forms, with work done by gravity ensuring energy conservation.

35. How does friction affect energy conservation?

Friction dissipates mechanical energy as heat, reducing the total kinetic and potential energy available.

36. How is the Work-Energy Theorem applied to elastic collisions?

In elastic collisions, kinetic energy is conserved, and the theorem explains the energy transfer between colliding objects.

37. What is the role of displacement in the theorem?

Displacement determines the amount of work done, directly influencing changes in kinetic energy.

38. How does the theorem apply to vehicles?

For vehicles, work done by the engine increases kinetic energy, while braking forces reduce it to bring the vehicle to rest.

39. What is the relationship between momentum and the Work-Energy Theorem?

While momentum focuses on force and time, the theorem links force and displacement, both describing motion changes.

40. How is work calculated for springs?

Work done on a spring is: where is the spring constant and is displacement.

41. How does the theorem explain projectile energy?

For projectiles, the theorem accounts for energy transformation between potential and kinetic forms during motion.

42. What is the work done in a closed loop?

In a closed loop under conservative forces, net work is zero since energy returns to its initial state.

43. How does the theorem relate to conservation of energy?

The theorem complements energy conservation by focusing on work and kinetic energy changes.

44. How does air drag affect kinetic energy?

Air drag reduces kinetic energy by doing negative work, decreasing the object’s velocity over time.

45. How does the theorem apply to springs in oscillation?

In oscillating springs, work alternates between kinetic and potential energy, conserving total mechanical energy.

46. How is work related to energy dissipation?

Work done by dissipative forces like friction converts mechanical energy into heat or other non-mechanical forms.

47. How does the theorem apply to turbines?

In turbines, work done by fluid forces changes rotational kinetic energy, generating mechanical power.

48. What is work done in uniform motion?

In uniform motion with no net force, net work is zero, and kinetic energy remains constant.

49. How does the theorem apply to stopping distances?

The theorem explains stopping distances by relating work done by braking forces to the kinetic energy reduction of the vehicle.

50. Why is the Work-Energy Theorem important?

The theorem provides a unifying framework for analyzing motion and energy changes, simplifying complex problems in mechanics and engineering.