Sociopolitical Structure

Sociopolitical Structure in 16th-Century Europe

Introduction

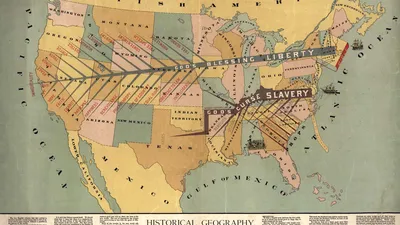

The sociopolitical structure of 16th-century Europe was a complex and dynamic system that laid the groundwork for the modern nation-state. This period was marked by significant transformations, including the decline of feudalism, the rise of centralized monarchies, the Protestant Reformation, and the emergence of the bourgeoisie. Understanding the sociopolitical structures of this era is crucial for comprehending the subsequent developments in European history, such as the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and the formation of contemporary political institutions.

For students of AP European History, grasping the intricacies of the 16th-century sociopolitical landscape is essential for analyzing the power dynamics, social hierarchies, and institutional changes that shaped Europe during this transformative period.

Defining Sociopolitical Structure

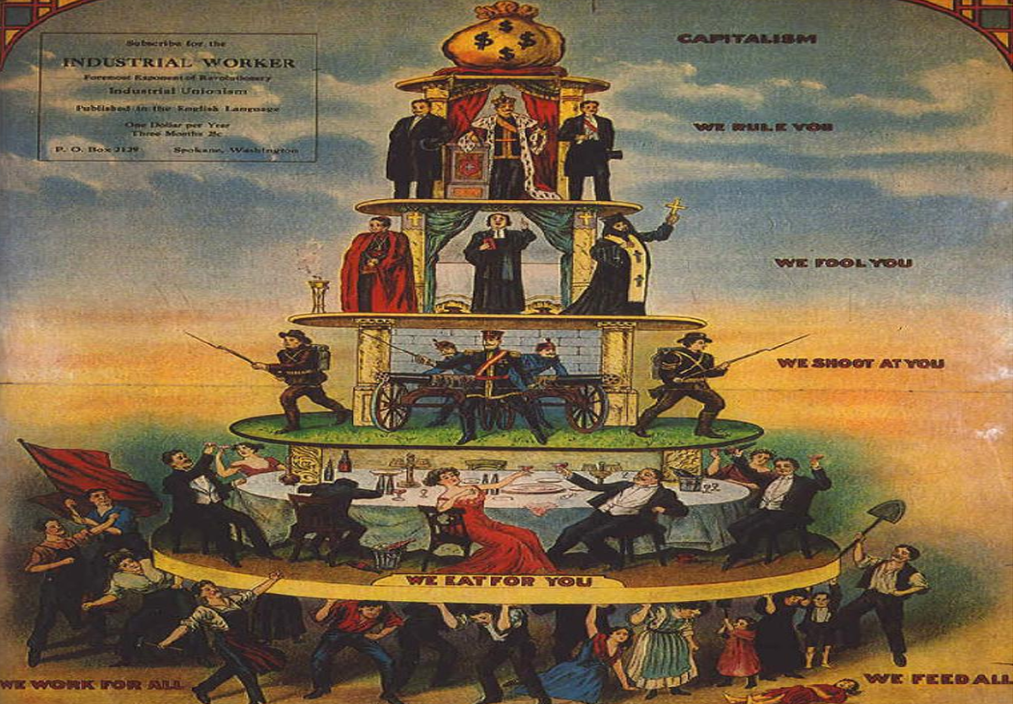

Sociopolitical structure refers to the organization and interaction of social and political elements within a society. It encompasses the relationships between different social classes, political authorities, institutions, and the distribution of power and resources. In the context of 16th-century Europe, the sociopolitical structure was characterized by a hierarchical system with the monarchy at its apex, supported by the nobility and the clergy, while emerging social classes like the bourgeoisie began to challenge traditional power dynamics.

Key Characteristics of Sociopolitical Structure

- Hierarchy: A clear ranking of social classes and political authority.

- Power Distribution: Allocation of power among monarchs, nobility, clergy, and emerging classes.

- Institutional Influence: The role of institutions such as the Church, state apparatus, and emerging nation-states.

- Social Stratification: Rigid class divisions impacting access to power, wealth, and privilege.

- Political Authority: The concentration of power in centralized monarchies versus decentralized feudal systems.

Understanding these characteristics helps in analyzing how different groups interacted, competed, and collaborated within the broader framework of European society during the 16th century.

Key Components of 16th-Century European Sociopolitical Structure

Feudalism

Definition: Feudalism was a decentralized political system prevalent in medieval Europe, where land ownership was the basis of power. Lords granted land (fiefs) to vassals in exchange for military service and loyalty.

Features:

- Hierarchy: Kings at the top, followed by powerful nobles, knights, and peasants.

- Land Ownership: Land was the primary source of wealth and power.

- Mutual Obligations: Lords provided protection; vassals offered military service.

- Decentralization: Political power was dispersed among various lords rather than centralized.

Impact: Feudalism created a rigid social hierarchy and limited the central authority of monarchs, leading to fragmented political power and frequent local conflicts.

Monarchy

Definition: Monarchy is a form of government where a single person, the monarch, holds supreme authority, often justified by the divine right of kings.

Features:

- Centralized Authority: Monarchs sought to consolidate power, reducing the influence of feudal lords.

- Divine Right: Monarchs claimed their authority was granted by God, making their rule unquestionable.

- Hereditary Succession: Power was typically passed down through royal families.

Impact: The rise of centralized monarchies weakened feudalism, leading to more unified and powerful nation-states.

Nobility

Definition: The nobility comprised the highest social class below the monarch, holding significant land and power.

Features:

- Land Ownership: Nobles owned vast estates and controlled the peasants working the land.

- Political Influence: They played crucial roles in governance and military leadership.

- Social Privileges: Nobles enjoyed exclusive rights and privileges, reinforcing their status.

Impact: Despite the rise of centralized monarchies, the nobility retained substantial power, often acting as intermediaries between the monarch and the lower classes.

Bourgeoisie

Definition: The bourgeoisie was the emerging middle class, primarily composed of merchants, tradespeople, and industrialists.

Features:

- Economic Power: They accumulated wealth through commerce, trade, and industry.

- Social Mobility: The bourgeoisie began to challenge traditional class structures, seeking greater political influence.

- Urban Centers: They were predominantly based in growing cities, driving urbanization and economic diversification.

Impact: The rise of the bourgeoisie signaled a shift towards a more capitalist economy and laid the foundation for future social and political revolutions.

Clergy

Definition: The clergy were religious leaders and institutions, primarily within the Catholic Church, holding significant spiritual and temporal power.

Features:

- Spiritual Authority: The Church wielded immense influence over religious and moral matters.

- Economic Power: The Church owned vast lands and accumulated wealth through tithes and donations.

- Political Influence: Clergy often held advisory roles in monarchies and influenced political decisions.

Impact: The Protestant Reformation challenged the Catholic Church’s dominance, leading to religious fragmentation and altering the sociopolitical landscape.

The Rise of Centralized Monarchies

Strengthening Royal Authority

During the 16th century, monarchs across Europe sought to centralize their authority, diminishing the power of feudal lords and establishing more cohesive and uniform governance structures.

Examples:

- France: King Francis I implemented administrative reforms to strengthen royal control.

- Spain: The unification of Castile and Aragon under Ferdinand and Isabella created a powerful centralized state.

- England: Henry VIII consolidated power, particularly through his break with the Catholic Church.

Outcomes:

- Unified States: Centralized monarchies led to the formation of more unified and powerful nation-states.

- Administrative Reforms: Establishment of bureaucracies and professional armies reduced reliance on feudal levies.

- Legal Standardization: Uniform laws and legal systems replaced the patchwork of local customs and laws.

Challenges to Feudalism

The centralization efforts often clashed with the established feudal system, as monarchs sought to reduce the autonomy of local lords and integrate their territories under direct royal control.

Strategies:

- Merit-Based Appointments: Monarchs appointed officials based on ability rather than birthright.

- Professional Armies: Transitioned from feudal levies to standing armies loyal to the monarch.

- Taxation Reforms: Implemented centralized taxation systems to fund royal activities and reduce dependence on feudal dues.

Impact:

- Diminished Feudal Power: Reduced the political and economic power of feudal lords.

- Enhanced Royal Authority: Strengthened the monarch’s control over national affairs and resources.

The Impact of the Protestant Reformation

Religious Fragmentation

The Protestant Reformation, initiated by figures like Martin Luther and John Calvin, led to significant religious and sociopolitical upheaval across Europe.

Key Points:

- Doctrinal Challenges: Reformation leaders challenged the Catholic Church’s doctrines, practices, and authority.

- Formation of Protestant Churches: New religious denominations emerged, including Lutheranism, Calvinism, and Anglicanism.

- Reduction of Catholic Hegemony: The Catholic Church’s influence waned as Protestantism gained followers.

Consequences:

- Religious Wars: Conflicts such as the Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) were rooted in religious tensions.

- Political Realignments: Monarchs aligned with either Catholic or Protestant factions, reshaping alliances and rivalries.

- Social Change: The Reformation encouraged literacy and individual interpretation of scriptures, fostering intellectual and cultural shifts.

Political Alliances and Conflicts

The Reformation altered the political landscape by creating new alliances based on religious affiliations, leading to both cooperation and conflict among European states.

Examples:

- Peace of Augsburg (1555): Allowed German princes to choose either Lutheranism or Catholicism, temporarily reducing religious conflict.

- Calvinist Influence: Calvinism spread to France, the Netherlands, and parts of Germany, influencing political movements and resistance against monarchical authority.

- English Reformation: Henry VIII’s break from the Catholic Church led to the establishment of the Church of England, affecting international alliances.

Impact:

- State Sovereignty: The Reformation contributed to the rise of the nation-state as religious authority became intertwined with political power.

- Decline of Papal Authority: Secular rulers asserted greater control over religious institutions within their territories.

- Increased State Power: Monarchs leveraged religious changes to consolidate their authority and diminish external influences.

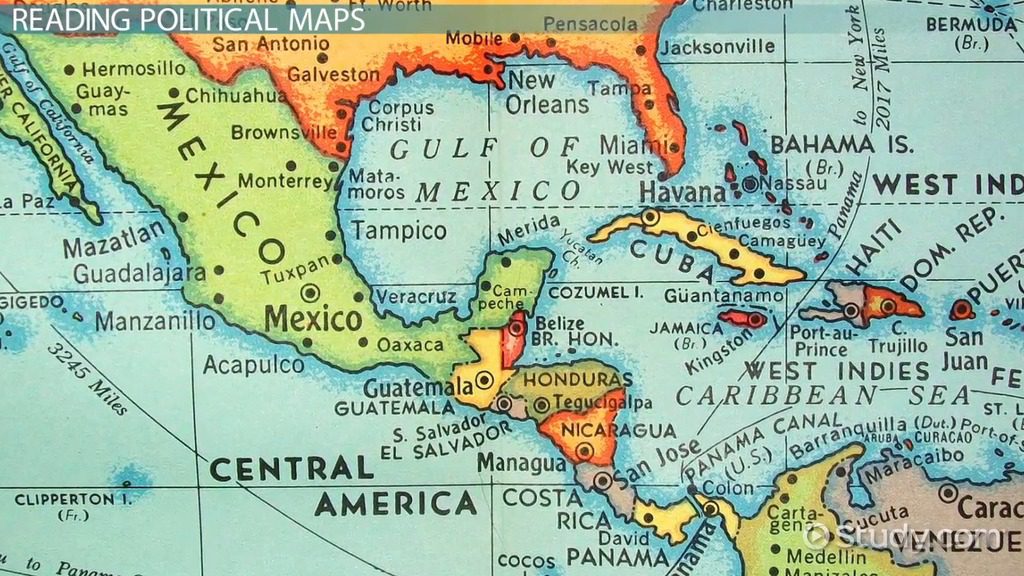

Emergence of Nation-States

Formation of Strong National Identities

The 16th century witnessed the emergence of nation-states with distinct national identities, driven by centralized monarchies, standardized languages, and cohesive cultural practices.

Factors:

- Centralized Governance: Unified political structures fostered a sense of national unity.

- Cultural Standardization: Promotion of a common language, literature, and cultural norms reinforced national identity.

- Economic Integration: Centralized economies and trade policies facilitated interdependence within the nation.

Examples:

- Spain: The unification under Ferdinand and Isabella created a powerful and cohesive Spanish state.

- France: Centralized administration under strong monarchs promoted French national identity.

- England: The establishment of the Church of England and centralized governance strengthened English identity.

Shifts in Alliances and Rivalries

As nation-states solidified, alliances and rivalries shifted based on political, religious, and economic interests, shaping European geopolitics.

Dynamics:

- Balancing Power: States sought to balance power to prevent any single nation from dominating Europe.

- Colonial Expansion: Competition for overseas territories intensified, leading to conflicts like the Anglo-Spanish War.

- Dynastic Marriages: Strategic marriages aimed to secure alliances and peace between rival states.

Impact:

- Frederick the Great and Absolutism: Strengthened states like Prussia through military and administrative reforms.

- Habsburg Dominance: The Habsburg dynasty expanded its influence, leading to conflicts with emerging nation-states.

- Dutch Independence: The Dutch Republic emerged as a major economic and naval power, challenging Spanish and Portuguese dominance.

Social Stratification and Class Divisions

Rigid Class Hierarchies

16th-century Europe was characterized by pronounced social stratification, with clear distinctions between the nobility, clergy, bourgeoisie, and peasants.

Social Classes:

- Monarchy: The ruling family holding supreme political authority.

- Nobility: High-ranking individuals owning large estates and wielding significant local power.

- Clergy: Religious leaders and institutions, particularly within the Catholic Church.

- Bourgeoisie: The emerging middle class engaged in trade, commerce, and early industrial activities.

- Peasantry: The largest social group, working the land and providing the economic foundation.

Characteristics:

- Limited Social Mobility: Movement between classes was difficult, often determined by birth.

- Privileges and Obligations: Each class had specific rights and responsibilities, reinforcing the hierarchical structure.

- Cultural Norms: Social behaviors and expectations were dictated by one’s class, maintaining the status quo.

Impact on Power, Wealth, and Privilege

The rigid class divisions had profound implications for access to power, wealth, and privilege, shaping the sociopolitical landscape of Europe.

Implications:

- Concentration of Wealth: Nobles and the clergy controlled substantial economic resources, while the peasantry had limited means.

- Political Influence: Higher social classes held more political power, influencing laws, governance, and policies.

- Social Control: The elite classes maintained control through laws, cultural norms, and institutions like the Church and military.

- Emerging Tensions: The rise of the bourgeoisie and increasing economic disparities began to challenge the established order, setting the stage for future social and political upheavals.

Long-Term Implications

Foundation for Modern European States

The sociopolitical transformations of the 16th century laid the groundwork for the development of modern European nation-states, characterized by centralized governance, standardized laws, and defined national identities.

Key Developments:

- Centralized Bureaucracies: Professional administrations replaced feudal systems, enhancing efficiency and control.

- Legal Systems: Uniform legal codes established consistency and fairness, reducing local arbitrary rule.

- National Identity: Shared languages, cultures, and histories fostered a sense of belonging and unity among citizens.

Influence on Future Political Movements

The sociopolitical changes of the 16th century influenced subsequent political movements, including the Enlightenment, revolutions, and the establishment of democratic institutions.

Examples:

- Enlightenment Ideals: Emphasis on reason, individualism, and secular governance stemmed from challenges to traditional authority structures.

- French Revolution: Social stratification and the rise of the bourgeoisie contributed to revolutionary fervor against the monarchy and aristocracy.

- Modern Democracy: Early forms of representative government in the Northern Colonies and nation-states influenced democratic practices and institutions.

Conclusion

The sociopolitical structure of 16th-century Europe was a tapestry of hierarchical relationships, centralized authority, and emerging social classes that collectively shaped the trajectory of European history. The decline of feudalism, rise of centralized monarchies, Protestant Reformation, and emergence of the bourgeoisie were pivotal in transforming the sociopolitical landscape, setting the stage for the modern nation-state and future political movements.

For students of AP European History, understanding these dynamics is essential for analyzing how power, wealth, and social structures evolved, leading to the complex and interconnected Europe we recognize today. The interplay between tradition and innovation, authority and rebellion, and unity and fragmentation during this period underscores the enduring impact of sociopolitical structures on historical development.

Practice Questions for Further Learning

- How did feudalism shape the sociopolitical structure of 16th-century Europe?

- In what ways did the Protestant Reformation impact the sociopolitical structure of Europe?

- Evaluate how the emergence of the bourgeoisie influenced the sociopolitical structure in 16th-century Europe.

- Compare and contrast the roles of monarchy and nobility in the 16th-century European sociopolitical structure.

- Analyze the relationship between centralized monarchies and the decline of feudalism.

- Discuss the role of the Catholic Church in maintaining the sociopolitical hierarchy of 16th-century Europe.

- How did the formation of nation-states alter political alliances and rivalries in Europe?

- Explain the social and economic factors that contributed to the rise of the bourgeoisie.

- What were the primary challenges faced by centralized monarchies in asserting authority over the nobility?

- Assess the impact of religious fragmentation on political stability in 16th-century Europe.

- How did social stratification affect access to power and wealth among different classes?

- What role did education and literacy play in the sociopolitical transformations of 16th-century Europe?

- Examine the influence of the Protestant Reformation on the development of modern European governance.

- How did the economic activities of the bourgeoisie challenge traditional power structures?

- What were the long-term consequences of the sociopolitical changes in 16th-century Europe on the modern nation-state?

- Discuss the interplay between economic diversification and political centralization in the Northern vs. Southern European states.

- How did the sociopolitical structure of 16th-century Europe contribute to the Age of Exploration and colonization?

- Evaluate the role of marriage alliances in strengthening or weakening monarchial power.

- How did the emergence of strong national identities influence international relations in 16th-century Europe?

- Predict how the sociopolitical structures established in the 16th century might have influenced subsequent historical events such as the Enlightenment or the French Revolution.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How did feudalism shape the sociopolitical structure of 16th-century Europe?

Answer:

Feudalism established a decentralized sociopolitical structure where local lords held significant power over their lands. This system created hierarchical relationships based on land ownership and loyalty, with vassals serving their lords in exchange for protection. As centralized monarchies began to rise, they started to weaken the feudal bonds, challenging the authority of local nobles and reshaping the political landscape toward more unified states.

2. In what ways did the Protestant Reformation impact the sociopolitical structure of Europe?

Answer:

The Protestant Reformation significantly disrupted the established sociopolitical structure by undermining the Catholic Church’s authority and leading to religious fragmentation. As different sects emerged, tensions rose between Catholic and Protestant states, influencing political alliances and conflicts. This shift allowed for the emergence of new forms of governance and increased participation from various social groups in political affairs.

3. Evaluate how the emergence of the bourgeoisie influenced the sociopolitical structure in 16th-century Europe.

Answer:

The emergence of the bourgeoisie during the 16th century marked a critical transformation in the sociopolitical structure. This growing middle class gained economic power through trade and commerce, challenging traditional nobility’s dominance. Their influence led to demands for political representation and rights, contributing to a gradual shift toward more inclusive governance models. The bourgeoisie’s aspirations played a pivotal role in shaping future revolutions and movements that sought greater equity in political power.

4. Compare and contrast the roles of monarchy and nobility in the 16th-century European sociopolitical structure.

Answer:

Monarchy:

- Centralized authority aiming to consolidate power.

- Implemented administrative and legal reforms to strengthen state control.

- Often justified power through divine right.

Nobility:

- Held significant local power and controlled vast lands.

- Served as intermediaries between the monarch and the peasantry.

- Maintained traditional feudal relationships and social hierarchies.

Contrast:

- Monarchs sought to centralize power, reducing the autonomy of the nobility.

- Nobles resisted centralization to maintain their local authority and privileges.

Similarity:

- Both were part of the elite class, holding substantial influence over political and social matters.

5. Analyze the relationship between centralized monarchies and the decline of feudalism.

Answer:

Centralized monarchies played a crucial role in the decline of feudalism by consolidating political power and reducing the autonomy of local lords. Monarchs implemented administrative reforms, established standing armies, and introduced uniform legal systems that diminished the feudal system’s decentralized nature. This shift led to more cohesive and powerful nation-states, replacing the fragmented feudal territories with centralized governance structures.

6. Discuss the role of the Catholic Church in maintaining the sociopolitical hierarchy of 16th-century Europe.

Answer:

The Catholic Church was a central institution in maintaining the sociopolitical hierarchy of 16th-century Europe. It wielded immense spiritual and temporal power, influencing monarchs, nobility, and the general populace. The Church’s doctrines and moral authority reinforced the existing social order, legitimizing the monarch’s rule through divine right. However, the Protestant Reformation challenged the Church’s dominance, leading to religious fragmentation and altering the sociopolitical landscape.

7. How did the formation of nation-states alter political alliances and rivalries in Europe?

Answer:

The formation of nation-states centralized political power and fostered strong national identities, which altered existing political alliances and rivalries. States aligned based on shared national interests, religion, and economic goals, leading to new diplomatic relationships and conflicts. The rise of powerful nation-states like Spain, France, and England intensified competition for dominance, colonial expansion, and influence, reshaping European geopolitics.

8. Explain the social and economic factors that contributed to the rise of the bourgeoisie.

Answer:

The rise of the bourgeoisie was driven by several social and economic factors:

- Economic Growth: Expansion of trade, commerce, and early industrial activities provided economic opportunities.

- Urbanization: Growth of cities facilitated the accumulation of wealth and the establishment of merchant and artisan classes.

- Decline of Feudalism: Reduced feudal obligations allowed individuals to engage more freely in business and trade.

- Education and Literacy: Increased access to education enabled the bourgeoisie to develop the skills necessary for economic and political influence.

- Technological Advancements: Innovations in production and transportation supported economic diversification.

9. What were the long-term consequences of the sociopolitical changes in 16th-century Europe on the modern nation-state?

Answer:

The sociopolitical changes of 16th-century Europe had profound long-term consequences on the development of modern nation-states:

- Centralized Governance: Established the foundation for modern bureaucratic states with centralized authority.

- Legal Systems: Standardized laws contributed to the creation of uniform legal frameworks.

- National Identity: Fostered a sense of national unity and identity that is essential for modern nation-states.

- Economic Policies: Laid the groundwork for capitalist economies through the rise of the bourgeoisie and trade expansion.

- Political Institutions: Influenced the development of democratic and representative institutions in later centuries.

10. How did religious conformity impact the Northern Colonies?

Answer:

Note: This question seems to be more relevant to AP US History content about the Northern Colonies rather than AP European History’s 16th-century Europe. However, in the European context, religious conformity, particularly under the influence of Puritanism, enforced strict moral codes and limited religious freedom for dissenters. This reinforced social order but also led to tensions and conflicts with those seeking greater religious diversity.

Related Terms

Feudalism: A decentralized political system where land ownership was the basis of power, with lords granting land to vassals in exchange for loyalty and military service.

Monarchy: A form of government where a single person, the monarch, holds supreme authority, often justified by divine right.

Bourgeoisie: The middle class that emerged during this period, primarily composed of merchants and tradespeople who played a crucial role in economic and social change.

Clergy: Religious leaders and institutions, particularly within the Catholic Church, holding significant spiritual and temporal power.

Protestant Reformation: A religious movement in the 16th century that led to the creation of Protestant churches and challenged the authority of the Catholic Church.

Nation-State: A political entity characterized by a centralized government, defined territory, and a strong sense of national identity.

Divine Right of Kings: The doctrine that monarchs derive their authority directly from God, not from their subjects.

Centralization: The process of consolidating political power and authority within a central government, reducing the autonomy of local lords.

Representative Government: A system of governance where officials are elected to represent the interests of the people.

Social Stratification: The division of society into hierarchical layers based on factors like wealth, power, and social status.

Enlightenment: An intellectual movement in the 17th and 18th centuries emphasizing reason, individualism, and skepticism of traditional authority.

Absolutism: A political doctrine advocating for the absolute sovereignty of the monarch, free from any checks or balances.

Guilds: Associations of artisans and merchants who controlled the practice of their craft in a particular town.

Habsburg Dynasty: A prominent royal house in Europe that controlled vast territories and played a significant role in European politics.

Peace of Augsburg (1555): An agreement allowing German princes to choose either Lutheranism or Catholicism as the official religion of their territories.

Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648): A devastating conflict primarily in Central Europe, rooted in religious tensions between Catholics and Protestants.

Divine Right: The belief that monarchs derive their authority directly from God, legitimizing their rule.

Mercantilism: An economic theory that trade generates wealth and is stimulated by the accumulation of profitable balances, applied in the Northern Colonies through trade and manufacturing.

Great Awakening: A series of religious revivals that swept through the colonies, including the Northern Colonies, influencing religious practices and fostering a sense of American identity.

Yankee: A term often associated with people from the Northern Colonies, embodying traits like industriousness, frugality, and independence.

Colonial Assembly: Legislative bodies established in the Northern Colonies, allowing for representative government and local decision-making.

Shipyards: Facilities in the Northern Colonies dedicated to building and repairing ships, crucial for trade and military defense.

Commonwealth: A political designation used by some Northern Colonies, such as Massachusetts, reflecting a focus on the common good and shared governance.

References

- Encyclopedia Britannica – Feudalism

- History.com – Protestant Reformation

- Khan Academy – 16th Century Europe

- The Balance – Centralization of Power

- Library of Congress – Reformation

- Investopedia – Bourgeoisie

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Protestant Reformation

- MIT OpenCourseWare – European History

- BBC Bitesize – Feudalism

- Oxford Academic – Sociopolitical Structures

- Cambridge University Press – European Monarchies

- National Geographic – Protestant Reformation

- Harvard University – Feudalism

- The British Library – The Reformation

- American Historical Association – The Rise of the Bourgeoisie

- Council for European Studies – 16th Century Europe

- YouTube – Sociopolitical Structures in 16th-Century Europe

- Economic History Review – Mercantilism

- National Archives – Peace of Augsburg

- Library of Congress – Thirty Years’ War

Recent Posts

- Geometry Regents Score Calculator (2025 NY Exam Tool)

- Algebra 2 Regents Score Calculator (2025 NY Exam Tool)

- Algebra 1 Regents Score Calculator (NY Regents Estimator)

- PreACT® Score Calculator (2025 Raw-to-Scaled Estimator)

- ACT® Score Calculator (2025 Raw-to-Scaled Score Tool)

- PSAT® Score Calculator (2025 Digital Exam Estimator Tool)

- AP® Music Theory Score Calculator (2025 Exam Estimator)

- AP® Art History Score Calculator (2025 Exam Estimator)

- AP® Spanish Literature Score Calculator (2025 Exam Tool)

- AP® Spanish Language Score Calculator (2025 Exam Tool)

- AP® Latin Score Calculator (2025 Exam Scoring Tool)

- AP® German Language Score Calculator (2025 Exam Tool)

- AP® French Language Score Calculator (2025 Exam Tool)

- AP® English Literature Score Calculator (2025 Exam Tool)

- AP® English Language Score Calculator (2025 Exam Tool)

Choose Topic

- ACT (17)

- AP (20)

- AP Art and Design (5)

- AP Chemistry (1)

- AP Physics 1 (1)

- AP Psychology (2025) (1)

- AP Score Calculators (35)

- AQA (5)

- Artificial intelligence (AI) (2)

- Banking and Finance (6)

- Biology (13)

- Business Ideas (68)

- Calculator (73)

- ChatGPT (1)

- Chemistry (3)

- Colleges Rankings (48)

- Computer Science (4)

- Conversion Tools (137)

- Cosmetic Procedures (50)

- Cryptocurrency (49)

- Digital SAT (3)

- Disease (393)

- Edexcel (4)

- English (1)

- Environmental Science (2)

- Etiology (7)

- Exam Updates (7)

- Finance (129)

- Fitness & Wellness (164)

- Free Learning Resources (208)

- GCSE (1)

- General Guides (40)

- Health (107)

- History and Social Sciences (152)

- IB (9)

- IGCSE (1)

- Image Converters (3)

- IMF (10)

- Math (44)

- Mental Health (58)

- News (9)

- OCR (1)

- Past Papers (450)

- Physics (5)

- Research Study (6)

- SAT (39)

- Schools (3)

- Sciences (1)

- Short Notes (5)

- Study Guides (28)

- Syllabus (19)

- Tools (1)

- Tutoring (1)

- What is? (312)

Recent Comments

4.2 Political Processes: Understanding the Shifts in Political Boundaries and Power Dynamics

4.4 Defining Political Boundaries

Geometry Regents Score Calculator (2025 NY Exam Tool)

Algebra 2 Regents Score Calculator (2025 NY Exam Tool)

Algebra 1 Regents Score Calculator (NY Regents Estimator)