Unit 2.2: Cell Structure and Function

Cells are the basic units of life, and the structure of their components plays a significant role in their function. In this post, we will dive into a few organelles and discuss how their specific structures contribute to their essential functions.

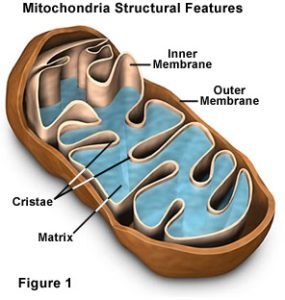

Mitochondria 🟢

The mitochondria are famously known as the “powerhouse of the cell.” They produce ATP, the energy currency for cellular processes. The mitochondria’s inner membrane is uniquely folded into structures called cristae, which significantly increase the surface area for chemical reactions. This increased surface area provides more space for the Electron Transport Chain (ETC) – an essential part of cellular respiration. With the ETC occurring on the cristae, the mitochondria can efficiently produce ATP to power the cell. The matrix, which is the space within the inner membrane, hosts the Krebs Cycle, allowing the products to move seamlessly to the ETC, promoting efficient energy production.

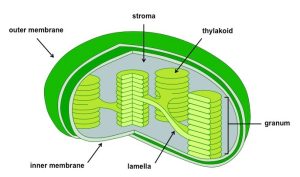

Chloroplast 🌿

Chloroplasts are organelles found in plant cells that conduct photosynthesis. The chloroplast has stacked thylakoid membranes that resemble a stack of coins called grana. These thylakoid membranes allow for an increase in surface area, enabling more efficient light absorption during the light-dependent reactions of photosynthesis. Photosystems and chlorophyll line the thylakoid membranes, capturing solar energy to facilitate the creation of glucose and other energy-storage molecules during photosynthesis. The stroma, a fluid inside the chloroplast, hosts the Calvin Cycle. The proximity of the stroma to the thylakoid membranes facilitates smooth interactions between the light-dependent reactions and the Calvin Cycle.

Plasma Membrane 🛡️

The plasma membrane, also known as the cell membrane, plays a vital role in maintaining cellular integrity and mediating transport. This membrane is composed of a phospholipid bilayer with embedded proteins, creating a semi-permeable barrier that regulates the movement of molecules in and out of the cell. The hydrophilic heads of the phospholipids face outward, interacting with water, while the hydrophobic tails face inward, avoiding water. This arrangement allows selective permeability, enabling the movement of small, nonpolar molecules and creating concentration gradients essential for cellular function. Larger or charged molecules require special transport proteins, some of which are channels, pumps, or carriers, to facilitate their movement across the membrane.

Lysosomes 💛

Lysosomes are the cell’s waste disposal system. These organelles are membrane-bound sacs filled with hydrolytic enzymes that digest excess or worn-out cell parts, bacteria, and food particles. The membrane surrounding the lysosome ensures that the digestive enzymes remain contained, preventing damage to other parts of the cell. These enzymes are crucial for breaking down macromolecules and recycling cellular components through a process called autophagy. The lysosome’s specialized membrane helps in binding with vesicles that need to be digested, thus playing a key role in cellular cleanup and turnover.

Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) 🏪

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) consists of the rough ER and the smooth ER, both of which play key roles in cell function. The rough ER is studded with ribosomes, which synthesize proteins. These proteins are packed into vesicles and sent to the Golgi apparatus for further processing and packaging. The smooth ER, on the other hand, lacks ribosomes and is involved in lipid synthesis, carbohydrate metabolism, and detoxification of drugs and poisons. It also stores calcium ions that are crucial for signaling within the cell.

Summary

The unique structure of each cellular organelle enables it to carry out its specific function effectively. Whether it’s the ATP production in the mitochondria or photosynthesis in the chloroplast, each organelle’s structure is directly related to its role. Understanding these relationships helps in appreciating the sophisticated functionality of cells, the basic building blocks of all living organisms.