Conservation of Linear Momentum and Collisions

Introduction

Momentum is a fundamental concept in physics that describes the motion of objects and systems. In Unit 4.3 of our exploration of mechanics, we delve into the Conservation of Linear Momentum and Collisions, two principles that have profound applications, from billiard games to rocket propulsion. Understanding these topics is not just a stepping stone in physics but also a key to mastering problem-solving across multiple disciplines.

Conservation of Linear Momentum

The Principle:

The total momentum of a closed system is conserved unless acted upon by an external force.

Mathematically, this can be expressed as:

Where:

represents momentum, a vector quantity defined as .

: Mass of the object

: Velocity of the object

Key Properties

Momentum Conservation in a System:

The total momentum of all interacting particles in a system remains constant if no external forces act.Elastic and Inelastic Collisions:

Momentum conservation applies to both, although energy behaves differently:Elastic Collision: Kinetic energy is conserved.

Inelastic Collision: Kinetic energy is not conserved.

Applications Beyond Collisions:

The principle applies to explosions, recoil problems (e.g., firing a gun), and more.

Why Is Momentum Conserved?

The conservation of momentum stems from Newton’s Third Law of Motion, which states:

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

In a system, forces exerted by particles on each other are equal and opposite, resulting in no net force. Thus, the total momentum remains unchanged.

Collisions: Types and Analysis

Collisions occur when two or more objects exert forces on each other over a short time. They’re categorized based on how kinetic energy behaves:

1. Elastic Collisions

Definition: Both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved.

Equation of Momentum Conservation:

m_1 v_{1i} + m_2 v_{2i} = m_1 v_{1f} + m_2 v_{2f} ]

Equation of Kinetic Energy Conservation:

\frac{1}{2} m_1 v_{1i}^2 + \frac{1}{2} m_2 v_{2i}^2 = \frac{1}{2} m_1 v_{1f}^2 + \frac{1}{2} m_2 v_{2f}^2 ]

Example:

Two billiard balls collide elastically. The velocities before and after can be determined using momentum and kinetic energy equations.

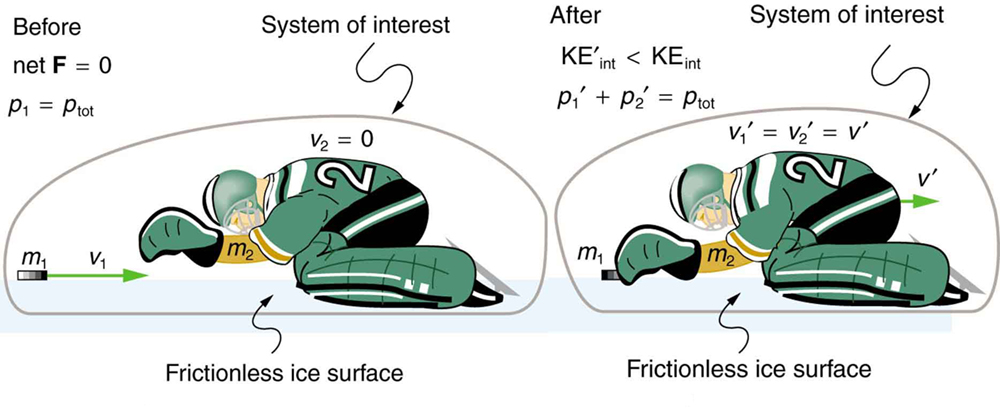

2. Inelastic Collisions

Definition: Momentum is conserved, but kinetic energy is not.

Perfectly Inelastic Collision: The colliding objects stick together after impact.

Equation:

m_1 v_{1i} + m_2 v_{2i} = (m_1 + m_2) v_f ]

Example:

Two cars collide and stick together. The combined velocity post-collision can be determined using the above equation.

3. Real-World Applications

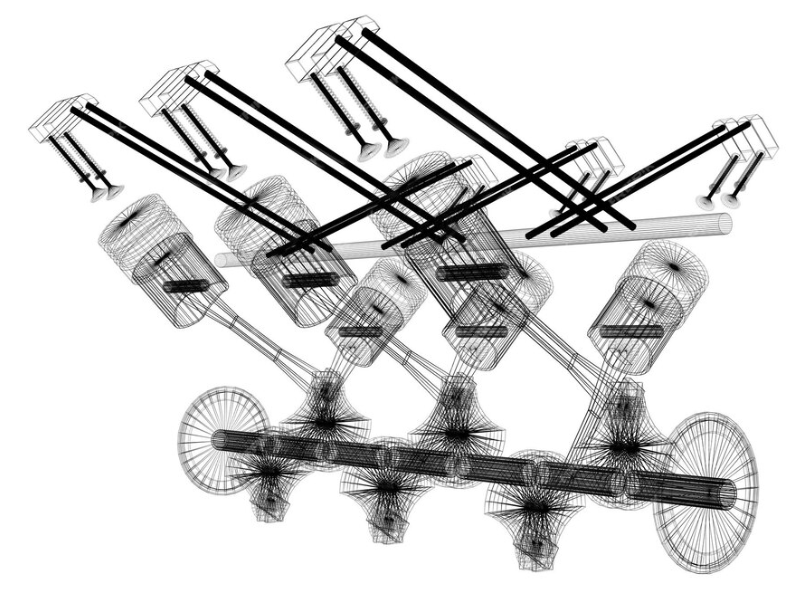

Rocket Propulsion

Rockets utilize the conservation of momentum by expelling exhaust gases backward, propelling themselves forward.

Sports

In games like pool or bowling, players exploit momentum transfer to achieve desired outcomes.

Solving Problems with Conservation of Momentum

Understand the System: Identify all objects involved and their initial conditions.

Write Momentum Equations: Apply the conservation principle.

Include Energy Equations (if applicable): For elastic collisions, account for kinetic energy.

Solve for Unknowns: Use algebra or calculus, depending on the complexity.

Check Units: Ensure consistent units throughout.

Practice Questions

Question 1: Elastic Collision

A 2 kg ball moving at 4 m/s collides elastically with a stationary 3 kg ball. Find the final velocities of both balls.

Solution:

Using:

and:

After solving, we get:

Final velocity of ball 1: 1 m/s

Final velocity of ball 2: 3 m/s

Question 2: Inelastic Collision

A 5 kg cart moving at 6 m/s collides and sticks to a stationary 2 kg cart. Find the final velocity of the combined system.

Solution:

Question 3: Explosion

A stationary object of mass 10 kg explodes into two fragments of masses 6 kg and 4 kg. The 6 kg fragment moves at 5 m/s. Find the velocity of the 4 kg fragment.

Solution:

(The negative sign indicates opposite direction.)

Conclusion

The conservation of linear momentum and collisions is a cornerstone of physics, offering profound insights into motion and interactions. Whether analyzing the trajectory of a rocket or the outcome of a car crash, understanding these principles equips you with the tools to solve real-world problems effectively. Mastering these concepts not only prepares you for exams but also deepens your appreciation of the physical laws governing the universe.

Conservation of Linear Momentum and Collisions FAQs

1. What is the conservation of linear momentum?

The conservation of linear momentum states that in a closed system with no external forces, the total linear momentum remains constant. Mathematically: where is momentum.

2. What is linear momentum?

Linear momentum is the product of an object’s mass and velocity, represented as: where:

is momentum,

is mass,

is velocity.

3. What are the conditions for momentum conservation?

Momentum is conserved if:

The system is isolated, meaning no external forces act on it.

Collisions or interactions involve only internal forces.

4. How is linear momentum conserved in collisions?

In collisions, the total momentum of the system before the collision equals the total momentum after the collision, irrespective of the type of collision.

5. What are elastic collisions?

Elastic collisions conserve both momentum and kinetic energy. The objects rebound without permanent deformation or energy loss.

6. What are inelastic collisions?

In inelastic collisions, momentum is conserved, but kinetic energy is not. Some energy is transformed into other forms, such as heat or sound.

7. What is a perfectly inelastic collision?

A perfectly inelastic collision is one where the colliding objects stick together after the collision, moving as a single entity.

8. What is the formula for momentum conservation in two-body collisions?

For two objects with masses and and velocities before collision and after collision:

9. What is impulse in the context of momentum?

Impulse is the change in momentum caused by a force acting over a time interval. It is calculated as:

10. How does impulse relate to collisions?

Impulse explains how forces during collisions change the momentum of the objects involved.

11. How is momentum conserved in explosions?

In explosions, the total momentum before and after the event remains the same if the system is isolated.

12. What is the center of mass in momentum conservation?

The center of mass is the point where the total mass of a system can be considered to act. In an isolated system, the center of mass moves with constant velocity.

13. How does momentum conservation apply to a ballistic pendulum?

In a ballistic pendulum, momentum conservation is used to calculate the initial velocity of a projectile based on the pendulum’s motion after impact.

14. What is the difference between elastic and inelastic collisions?

Elastic: Both momentum and kinetic energy are conserved.

Inelastic: Only momentum is conserved; kinetic energy is partially converted into other forms.

15. How is kinetic energy affected in inelastic collisions?

In inelastic collisions, some kinetic energy is transformed into heat, sound, or deformation energy, reducing the total kinetic energy.

16. How does momentum conservation apply to two-dimensional collisions?

In two-dimensional collisions, momentum is conserved separately along each axis:

17. How does rotational motion affect linear momentum conservation?

Linear momentum conservation applies to translational motion, while angular momentum conservation applies to rotational motion. Both can coexist in systems.

18. How is momentum conserved in a rocket propulsion system?

Momentum conservation explains rocket motion: the momentum of expelled gases equals the forward momentum of the rocket.

19. What is the coefficient of restitution in collisions?

The coefficient of restitution () measures the elasticity of a collision:

: Perfectly elastic collision.

: Perfectly inelastic collision.

20. How does momentum conservation explain recoil?

Recoil occurs because the momentum of the expelled projectile (e.g., bullet) is equal and opposite to the momentum of the recoiling object (e.g., gun).

21. How is momentum conserved in billiard ball collisions?

In billiard ball collisions, momentum conservation predicts the velocities and directions of balls after collision.

22. What is the role of external forces in momentum conservation?

External forces disrupt momentum conservation. For conservation to hold, the system must be isolated from external influences.

23. How does momentum conservation apply to vehicles?

In vehicle collisions, momentum conservation helps analyze crash dynamics, estimating velocities before and after impact.

24. How does the mass ratio affect collision outcomes?

When two objects with different masses collide, the less massive object experiences a greater change in velocity, while the more massive object changes velocity less.

25. How is momentum conserved in particle physics?

In particle collisions, momentum conservation helps predict the directions and energies of resultant particles.

26. How does air resistance affect momentum conservation?

Air resistance acts as an external force, reducing the momentum of objects and violating strict conservation unless accounted for.

27. How is momentum conserved in a pendulum?

In pendulum systems, momentum conservation applies during interactions like collisions with other objects.

28. How does momentum conservation apply to space physics?

In space, isolated systems like spacecraft and satellites conserve momentum, allowing predictions of motion during maneuvers.

29. How is momentum conserved in explosions?

In an explosion, the total momentum before and after the event remains constant, with fragments moving in opposite directions.

30. What is the impulse-momentum theorem?

The theorem states that impulse equals the change in momentum:

31. How does momentum conservation explain pool shots?

In pool, momentum conservation predicts how balls scatter after impact, considering their masses and velocities.

32. What is the relationship between momentum and energy in collisions?

Momentum is always conserved, while kinetic energy is only conserved in elastic collisions.

33. How does momentum conservation apply to explosions?

In explosions, the system’s total momentum is conserved, with the momentum of fragments balancing out.

34. What is a head-on collision?

A head-on collision occurs when two objects move directly toward each other, making the analysis simpler due to alignment along a single axis.

35. How does friction affect momentum conservation?

Friction acts as an external force, disrupting momentum conservation unless it is negligible or counteracted.

36. How is momentum conserved in multi-body systems?

In multi-body systems, the vector sum of all individual momenta remains constant in the absence of external forces.

37. How does momentum conservation apply to railway coupling?

In railway coupling, momentum conservation calculates the combined velocity of coupled cars after collision.

38. How is momentum conserved in liquid flows?

In fluid dynamics, momentum conservation explains how liquids react to forces, such as in propulsion or channel flows.

39. What is the momentum of a system of particles?

The total momentum of a system is the vector sum of the momenta of all particles:

40. How does momentum conservation apply to rotating systems?

In rotating systems, the translational momentum of the center of mass and the rotational motion around it are analyzed separately.

41. How does momentum conservation explain tandem jumps?

In tandem jumps, such as skydiving, the combined momentum before and after the jump remains constant.

42. How is momentum conserved in two-dimensional explosions?

Momentum is conserved along each axis independently, allowing analysis of fragment motion in two-dimensional space.

43. How does elasticity affect collision outcomes?

Elasticity determines how much kinetic energy is conserved, influencing post-collision velocities and directions.

44. What is the significance of relative velocity in collisions?

Relative velocity helps calculate the coefficient of restitution, which quantifies elasticity in collisions.

45. How does momentum conservation apply to air collisions?

Momentum conservation explains the dynamics of mid-air collisions, such as those involving aircraft or drones.

46. How does momentum conservation relate to center of mass motion?

The center of mass of an isolated system moves with constant velocity, reflecting the conservation of total momentum.

47. What is the importance of momentum conservation in engineering?

Momentum conservation is crucial for designing safer vehicles, understanding fluid flows, and analyzing structural impacts.

48. How does momentum conservation apply to lifting systems?

Momentum conservation helps analyze the forces and velocities involved when lifting or lowering loads using pulleys or cranes.

49. How does momentum conservation explain energy loss in inelastic collisions?

While momentum is conserved, some kinetic energy converts to heat, sound, or deformation energy, reducing total mechanical energy.

50. Why is understanding momentum conservation important?

Understanding momentum conservation is vital for solving real-world problems in mechanics, engineering, astrophysics, and everyday applications, ensuring accurate predictions and efficient designs.