Acid-Base Reactions and Buffers: The Essentials for Chemistry Students

Acid-base reactions form a cornerstone of chemistry, leading to fascinating phenomena like the creation of buffers—solutions that resist drastic changes in pH. In this guide, we’ll break down key concepts of strong and weak acid-base reactions and introduce the fundamentals of buffer solutions, explaining how they help maintain pH stability in chemical and biological systems.

Understanding Buffers

What are Buffers?

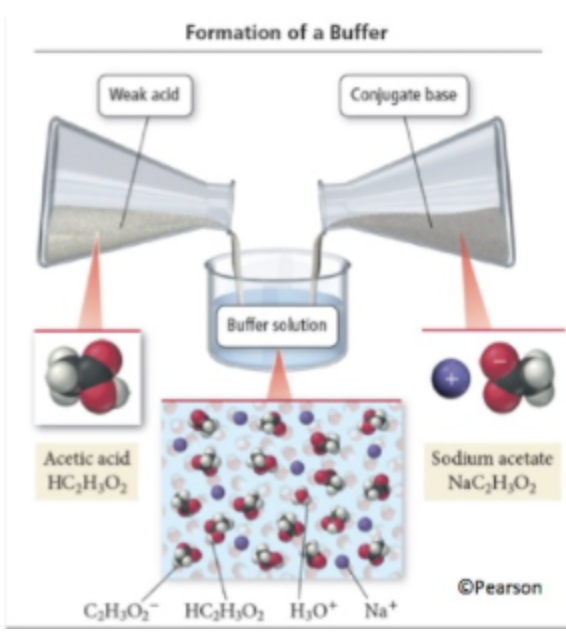

Buffers are solutions containing a weak acid and its conjugate base (or a weak base and its conjugate acid). They resist significant pH changes when small amounts of acid or base are added. This resistance occurs because the acid can neutralize added bases, while the conjugate base can neutralize added acids. This unique property makes buffers essential for maintaining homeostasis in biological systems, such as human blood, which acts as a buffer to maintain a stable pH.

Image From UOregon

Example:

A buffer containing acetic acid (CH₃COOH) and its conjugate base acetate (CH₃COO⁻) can resist pH changes as follows:

- Adding an acid: The acetate ion (CH₃COO⁻) neutralizes excess H⁺ ions.

- Adding a base: The acetic acid (CH₃COOH) donates H⁺ ions to neutralize the base.

Acid-Base Reactions

Strong Acid-Strong Base Reactions

These reactions proceed to completion, meaning all the acid and base react to form a salt and water. For example, the reaction between HCl (hydrochloric acid) and NaOH (sodium hydroxide): HCl + NaOH → NaCl + H₂O

Example Problem:

What is the pH after adding 10.0 mL of 0.100 M NaOH to 25.0 mL of 0.100 M HCl?

Step-by-Step Solution:

Reaction Equation:

HCl + NaOH → NaCl + H₂O

Net Ionic Equation:

H⁺ + OH⁻ → H₂OCalculate Millimoles:

- NaOH: 10.0 mL × 0.100 M = 1 mmol OH⁻

- HCl: 25.0 mL × 0.100 M = 2.5 mmol H⁺

Use Stoichiometry:

Since H⁺ is in excess, the remaining H⁺ is 1.5 mmol.Calculate [H⁺]:

[H⁺] = 1.5 mmol / 35 mL = 4.3 × 10⁻² M

pH = -log(4.3 × 10⁻²) ≈ 1.37

Key Zones of Reaction:

- Acid in excess

- Base in excess

- Equivalence point (equal moles of acid and base)

Weak Acid-Strong Base Reactions

In these reactions, the weak acid only partially dissociates, meaning the reaction reaches equilibrium. Consider the reaction between acetic acid (CH₃COOH) and NaOH: CH₃COOH + NaOH → CH₃COONa + H₂O

Example Problem:

Calculate the pH after adding 10.0 mL of 0.100 M NaOH to 25.0 mL of 0.100 M acetic acid.

Step-by-Step Solution:

Reaction Equation:

CH₃COOH + NaOH → CH₃COONa + H₂O

Net Ionic Equation:

CH₃COOH + OH⁻ → CH₃COO⁻ + H₂OCalculate Millimoles:

- NaOH: 10.0 mL × 0.100 M = 1 mmol OH⁻

- CH₃COOH: 25.0 mL × 0.100 M = 2.5 mmol CH₃COOH

Use Stoichiometry:

- Remaining CH₃COOH: 1.5 mmol

- Produced CH₃COO⁻: 1 mmol

Calculate pH using the Henderson-Hasselbalch Equation:

pH = pKa + log([CH₃COO⁻]/[CH₃COOH])

Given pKa of acetic acid ≈ 4.76:

pH = 4.76 + log(1/1.5) ≈ 4.48

Buffers in Action

Buffers help stabilize pH by neutralizing small additions of acids or bases. They are most effective when the concentrations of the weak acid and its conjugate base are nearly equal, providing a buffering capacity around the acid’s pKa.

Key Takeaways

- Strong acid-strong base reactions go to completion, producing water and salt.

- Weak acid-strong base reactions reach equilibrium, creating a mixture of acid and conjugate base—a buffer.

- Buffers resist changes in pH, maintaining stability in both biological and chemical systems.