Amyloid

Below is a comprehensive, structured report on amyloid, which encompasses the abnormal protein deposits associated with various types of amyloidosis. This report covers its definition, historical background, clinical manifestations, underlying causes, risk factors, complications, diagnostic methods, treatment options, prevention strategies, global statistics, recent research, and interesting insights.

1. Overview

What is Amyloid?

Amyloid refers to misfolded protein aggregates that accumulate extracellularly in tissues and organs. These insoluble fibrils have a characteristic β-pleated sheet structure that can be identified by specific histological stains.

Definition and Affected Body Parts/Organs

- Definition:

Amyloid deposits are abnormal protein aggregates formed when normally soluble proteins misfold and aggregate into insoluble fibrils. They can accumulate in various tissues, causing organ dysfunction—a process known as amyloidosis. - Affected Organs:

- Heart: Amyloid deposition can lead to restrictive cardiomyopathy and heart failure.

- Kidneys: Often involved in renal amyloidosis, leading to proteinuria and eventual renal failure.

- Nervous System: Can affect peripheral nerves and cause neuropathies; in some cases, central nervous system involvement occurs.

- Gastrointestinal Tract, Liver, and Spleen: These organs may also be affected depending on the type of amyloidosis.

Prevalence and Significance of the Disease

- Prevalence:

Amyloidosis is considered a rare disease, though its incidence varies by type (e.g., AL amyloidosis, transthyretin amyloidosis). - Significance:

- Amyloid deposition can lead to progressive organ dysfunction and, if untreated, significant morbidity and mortality.

- Early detection is critical for managing the disease and improving outcomes.

2. History & Discoveries

When and How Was Amyloid First Identified?

- The term “amyloid” was introduced in the 19th century when pathologists observed a substance in tissues that stained like starch.

- In 1854, Rudolf Virchow coined the term “amyloid” (meaning “starch-like”) based on its staining properties, though it was later understood to be proteinaceous.

Who Discovered It?

- While Virchow’s work was pivotal in naming the substance, subsequent researchers clarified its biochemical nature and role in disease. No single individual is credited with “discovering” amyloid deposits; it was a progressive evolution of understanding.

Major Discoveries and Breakthroughs

- Histological Techniques:

- The development of Congo red staining and the observation of apple-green birefringence under polarized light were major breakthroughs in diagnosing amyloid.

- Biochemical Identification:

- Later studies revealed that amyloid deposits are composed of misfolded proteins with β-pleated sheet structures.

- Classification:

- Advances in molecular biology have led to the classification of amyloidosis into various types, such as AL (light-chain), AA (serum amyloid A), and ATTR (transthyretin) amyloidosis.

- Treatment Evolution:

- The introduction of chemotherapy for AL amyloidosis and novel therapies like TTR stabilizers for ATTR has transformed patient management.

Evolution of Medical Understanding Over Time

- Initial views of amyloid were limited to histological observations. Today, we understand the molecular basis of amyloid formation and its clinical implications, paving the way for targeted therapies and improved diagnostic methods.

3. Symptoms

Early Symptoms vs. Advanced-Stage Symptoms

- Early Symptoms:

- Often nonspecific, such as fatigue, weight loss, and mild organ dysfunction.

- In AL amyloidosis, early signs might include unexplained edema or peripheral neuropathy.

- Advanced-Stage Symptoms:

- Cardiac involvement can lead to shortness of breath, irregular heart rhythms, and heart failure.

- Renal involvement may result in significant proteinuria, edema, and renal failure.

- Neurological symptoms can progress to severe neuropathy, affecting mobility and sensation.

Common vs. Rare Symptoms

- Common: Fatigue, weight loss, and symptoms related to the affected organ (e.g., shortness of breath in cardiac amyloidosis).

- Rare: Specific signs such as macroglossia (enlarged tongue) or periorbital purpura, which are more characteristic of certain forms of amyloidosis.

How Symptoms Progress Over Time

- Amyloidosis is typically a progressive condition. Early, subtle symptoms may be overlooked until significant organ deposition occurs, at which point clinical manifestations can become severe and potentially life-threatening.

4. Causes

Biological and Environmental Causes

- Biological Causes:

- Abnormal protein folding leads to the formation of amyloid fibrils.

- In AL amyloidosis, plasma cells produce abnormal light chains that misfold and aggregate.

- In AA amyloidosis, chronic inflammation elevates serum amyloid A protein, which can deposit in tissues.

- ATTR amyloidosis results from misfolded transthyretin protein, either due to genetic mutations or age-related changes.

- Environmental Causes:

- Chronic inflammatory conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis) can predispose individuals to AA amyloidosis.

Genetic and Hereditary Factors

- Hereditary ATTR Amyloidosis:

- Caused by mutations in the transthyretin (TTR) gene, leading to familial amyloid polyneuropathy or cardiomyopathy.

- Genetic predisposition plays a significant role in certain types of amyloidosis.

Any Known Triggers or Exposure Risks

- Triggers may include chronic infections, inflammatory diseases, and genetic mutations.

- Exposure risks are more related to underlying conditions rather than external environmental toxins.

5. Risk Factors

Who Is Most at Risk?

- Age:

- The risk increases with age, particularly for senile systemic amyloidosis (wild-type ATTR).

- Gender:

- Some forms of amyloidosis, like AL amyloidosis, have a slight male predominance, whereas others, like familial ATTR, may show variable gender distribution.

- Occupation & Lifestyle:

- There are no direct occupational risks; however, lifestyle factors that contribute to chronic inflammation (e.g., obesity, smoking) may indirectly increase risk.

- Other Factors:

- Individuals with chronic inflammatory conditions or a family history of amyloidosis are at higher risk.

Environmental, Occupational, and Genetic Influences

- Genetic predisposition is a key factor in hereditary forms.

- Environmental factors, such as chronic infections or inflammatory states, contribute mainly to AA amyloidosis.

Impact of Pre-existing Conditions

- Pre-existing conditions like chronic inflammatory diseases, plasma cell disorders (multiple myeloma), or long-standing heart failure can predispose individuals to develop amyloidosis.

6. Complications

What Complications Can Arise from Amyloid Deposition?

- Organ Dysfunction:

- Cardiac amyloidosis can lead to heart failure, arrhythmias, and sudden cardiac death.

- Renal amyloidosis may result in nephrotic syndrome and progressive renal failure.

- Neurological involvement can cause debilitating peripheral neuropathy.

- Systemic Effects:

- Multi-organ failure in advanced stages.

- Long-Term Impact on Organs and Overall Health:

- Progressive deposition leads to irreversible damage and dysfunction, significantly affecting quality of life.

- Potential Disability or Fatality Rates:

- Complications of amyloidosis can be life-threatening, particularly with cardiac involvement, and are a major cause of mortality in affected patients.

7. Diagnosis & Testing

Common Diagnostic Procedures

- Clinical Evaluation:

- Detailed patient history and physical examination focusing on symptoms and affected organs.

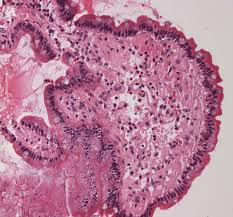

- Biopsy:

- Tissue biopsy (e.g., from abdominal fat pad, kidney, or heart) with Congo red staining to detect amyloid deposits (apple-green birefringence under polarized light).

- Imaging:

- Echocardiography, MRI, and nuclear imaging (e.g., technetium-labeled scans) to assess cardiac involvement.

Medical Tests

- Blood Tests:

- Measurement of free light chains, serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP), and immunofixation electrophoresis (IFE) for AL amyloidosis.

- Genetic Testing:

- For suspected hereditary ATTR amyloidosis, genetic analysis of the TTR gene.

Early Detection Methods and Their Effectiveness

- Early diagnosis is achieved by combining clinical suspicion with biopsy and specialized imaging, which are highly effective in detecting amyloid deposits before irreversible organ damage occurs.

8. Treatment Options

Standard Treatment Protocols

- For AL Amyloidosis:

- Chemotherapy (e.g., melphalan, dexamethasone) to reduce abnormal plasma cell production.

- Autologous stem cell transplant in eligible patients.

- For ATTR Amyloidosis:

- TTR stabilizers (e.g., tafamidis) to prevent misfolding.

- TTR gene silencers (e.g., patisiran, inotersen) to reduce production of the protein.

- Supportive Care:

- Management of heart failure, renal support, and symptom relief.

Medications, Surgeries, and Therapies

- Medications:

- Specific regimens depend on the type of amyloidosis; new therapies such as monoclonal antibodies targeting amyloid deposits are under development.

- Surgical Interventions:

- In cases of advanced organ failure, supportive surgeries or transplant may be considered.

- Emerging Treatments and Clinical Trials:

- Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating novel agents, including gene therapy and RNA interference techniques, to further improve outcomes.

9. Prevention & Precautionary Measures

How Can Amyloidosis Be Prevented?

- Primary Prevention:

- There is no direct prevention for amyloidosis; however, managing underlying conditions (e.g., chronic inflammation, plasma cell disorders) can reduce risk.

- Lifestyle Changes:

- Maintaining a healthy lifestyle and early treatment of inflammatory or autoimmune conditions.

- Environmental Precautions:

- Reducing exposure to factors that exacerbate chronic inflammatory diseases.

- Preventive Screenings:

- Regular screening in high-risk populations (e.g., those with multiple myeloma or familial history of amyloidosis) for early detection.

- Vaccines:

- No vaccines exist for amyloidosis; prevention focuses on early diagnosis and management of risk factors.

10. Global & Regional Statistics

Incidence and Prevalence Rates Globally

- The overall prevalence of amyloidosis varies by type. AL amyloidosis is rare, with estimates of 8–12 cases per million per year, while wild-type ATTR (senile systemic amyloidosis) is more common in the elderly.

- Regional differences exist due to genetic, environmental, and diagnostic factors.

Mortality and Survival Rates

- Prognosis varies widely by type and stage. Early detection and treatment can improve survival, but advanced cardiac amyloidosis carries a high mortality risk.

Country-Wise Comparison and Trends

- Developed countries generally report higher diagnostic rates due to advanced healthcare systems.

- In regions with limited diagnostic capabilities, the prevalence may be underestimated, and outcomes are poorer due to delayed treatment.

11. Recent Research & Future Prospects

Latest Advancements in Treatment and Research

- New Therapeutic Agents:

- TTR stabilizers and gene silencers are transforming the management of ATTR amyloidosis.

- Biologic and Immunomodulatory Therapies:

- Emerging monoclonal antibodies and small molecules are being studied to clear amyloid deposits.

- Personalized Medicine:

- Genetic and biomarker studies are enhancing individualized treatment strategies.

Ongoing Studies and Future Medical Possibilities

- Numerous clinical trials are underway to evaluate next-generation treatments, including RNA interference and gene-editing techniques.

- Future research is focused on earlier diagnosis and improving the quality of life for patients with amyloidosis.

Potential Cures or Innovative Therapies Under Development

- While a complete cure remains elusive, advances in targeted therapies and immunotherapy hold promise for significantly altering the disease course and reducing morbidity.

12. Interesting Facts & Lesser-Known Insights

Uncommon Knowledge About Amyloid

- Apple-Green Birefringence:

- A key diagnostic hallmark of amyloid deposits is the apple-green birefringence seen under polarized light after Congo red staining.

- Myths vs. Medical Facts:

- A common misconception is that all amyloid deposits are the same; in reality, amyloidosis encompasses a range of disorders with different protein types and clinical outcomes.

- Impact on Specific Populations:

- Hereditary forms of ATTR amyloidosis can manifest at a relatively young age and affect multiple family members.

- Historical Curiosities:

- The term “amyloid” was coined in the 19th century by Rudolf Virchow, who mistakenly believed the deposits resembled starch.

- Economic and Social Impact:

- Although rare, amyloidosis has a high economic burden due to the costs of chronic management and advanced therapies.

References

- Mayo Clinic. (2023). Amyloidosis: Overview, Diagnosis, and Treatment.

- National Institutes of Health. (2022). Advances in Amyloid Research and Clinical Management.

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. (2023). Understanding Amyloidosis: Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments.

- UpToDate. (2023). Diagnosis and Management of Amyloidosis.

- Global Health Statistics. (2023). Epidemiology of Amyloidosis Worldwide.

- World Health Organization. (2023). Guidelines for the Management of Rare Diseases.

- Nature Reviews. (2023). Emerging Therapeutic Approaches in Amyloidosis.

- BMJ. (2023). Amyloidosis: Myths, Realities, and Future Directions.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2023). Ongoing Studies in Amyloidosis Treatment.

This detailed report on amyloid provides an in-depth overview of its definition, historical evolution, clinical manifestations, underlying causes, risk factors, complications, diagnostic approaches, treatment strategies, and future research directions. Early detection and targeted therapies remain essential in managing amyloidosis and improving patient outcomes.

4.1 Attribution Theory and Person Perception: Why We Judge People the Way We Do (Even When We’re Totally Wrong) Let’s be honest. We’ve all

4.1 Attribution Theory and Person Perception: Why We Judge People the Way We Do (Even When We’re Totally Wrong) Let’s be honest. We’ve all