The Trans-Saharan Trade Routes: A Complete Guide

The Trans-Saharan trade routes were one of the most significant trade networks in global history, connecting the Mediterranean coast to West Africa and the sub-Saharan region. These routes traversed the vast Sahara Desert, facilitating the exchange of goods, cultures, and ideas while shaping the economic, political, and cultural landscapes of Africa. Let’s explore the causes, technologies, cultural exchanges, and the empires that rose to prominence through this historic network.

What Were the Trans-Saharan Trade Routes?

The Trans-Saharan trade routes comprised a network of pathways that allowed merchants to traverse the challenging terrain of the Sahara Desert. These routes connected regions such as North Africa, the Mediterranean, and the West African savannah, enabling the movement of goods such as gold, salt, ivory, and slaves. This trade network emerged as a vital part of the global economy and persisted for centuries, shaping African and world history.

The routes were not just economic lifelines but also conduits for cultural exchange, spreading ideas, religions, and technologies across vast distances. They were used by ancient civilizations such as the Romans, medieval Arab empires, and the great African kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai. Even as modern transportation systems emerged, the legacy of the Trans-Saharan trade routes continues to influence the region.

Why Were the Trans-Saharan Trade Routes Important?

The Trans-Saharan trade routes were instrumental in fostering economic growth, cultural exchange, and political power in Africa. Their importance can be categorized into the following key areas:

Economic Impact

Wealth Generation: The trade routes brought immense wealth to regions involved in the exchange of valuable commodities like gold and salt.

Trade Expansion: These routes connected Africa to global trade networks, facilitating commerce between the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and sub-Saharan Africa.

Cultural Exchange

Spread of Religions: Islam spread across Africa via the trade routes, influencing cultures, languages, and governance.

Diasporic Communities: Merchants established communities in foreign lands, introducing their traditions and fostering multicultural societies.

Technological and Social Advancements

Camel Domestication: The use of camels revolutionized desert travel, enabling long-distance trade.

Knowledge Transfer: Traders introduced new technologies and ideas, such as ironworking and the compass, to Africa.

Political Influence

Formation of Empires: Wealth generated from trade routes contributed to the rise of powerful empires like Mali, Ghana, and Songhai.

Control of Trade Routes: Empires gained political power by controlling key trade hubs, solidifying their dominance.

Causes of Trans-Saharan Trade

The emergence and growth of the Trans-Saharan trade routes can be attributed to several factors:

Geography

Strategic Location: The Sahara acted as both a barrier and a bridge, connecting the Mediterranean world with sub-Saharan Africa.

Rich Resources: West Africa’s abundance of gold and the Sahara’s salt mines made trade lucrative.

Technological Advancements

Camel Domestication: Camels, brought to Africa by Arab traders, revolutionized desert travel. Their ability to carry heavy loads and endure long journeys with minimal water made them indispensable for trade.

Camel Saddles: Innovations in saddle design allowed merchants to transport goods more efficiently, facilitating larger caravans.

Demand for Goods

Gold and Salt: Gold from West Africa and salt from the Sahara were highly sought after in Mediterranean markets.

Luxury Goods: Ivory, slaves, and exotic goods from Africa attracted traders from distant regions.

Technologies and Innovations of the Trans-Saharan Trade

Camels and Saddles

The introduction of camels to Africa revolutionized trade. These animals, known as the “ships of the desert,” could travel up to 25 miles per day, carrying loads of 300 pounds while requiring minimal water. The Berbers, indigenous to North Africa, developed specialized camel saddles that allowed for the efficient transport of goods and riders.

Caravans

Caravans were large groups of traders and their camels, traveling together for safety and efficiency. These caravans often included hundreds of camels, enabling the transportation of vast quantities of goods across the desert. They also served as social and cultural institutions, fostering camaraderie among traders and ensuring protection against bandits.

Cultural Exchange Along the Trans-Saharan Trade Routes

The Trans-Saharan trade routes were more than just conduits for goods; they were highways of cultural exchange that profoundly impacted Africa and beyond:

Formation of Diasporic Communities

Merchant Settlements: West African merchants settled in cities like Cairo, creating vibrant diasporic communities. These settlers brought their languages, traditions, and economic expertise, enriching local cultures.

Slave Diaspora: The trade routes also facilitated the forced migration of African slaves to the Middle East, Europe, and later the Americas, leaving a lasting impact on global demographics.

Spread of Islam

Islam spread to West Africa through Arab and Berber traders. By the 8th century, Islamic teachings had reached regions like Mali and Ghana, where they found fertile ground. Rulers and elites adopted Islam, establishing centers of learning and promoting the construction of mosques and Islamic schools.

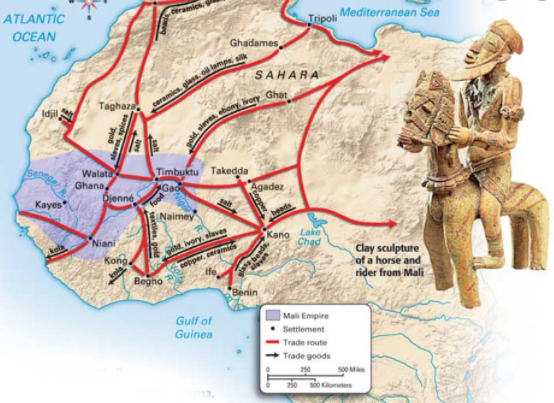

Major Empires of the Trans-Saharan Trade

Several powerful empires rose to prominence due to their control of the Trans-Saharan trade routes. Let’s explore their contributions:

Ghana Empire

Economic Power: Ghana controlled the trade of gold and salt, amassing immense wealth.

Military Strength: The empire’s military protected trade routes, ensuring safe passage for merchants.

Trade Centers: Cities like Kumbi Saleh became bustling trade hubs.

Mali Empire

Golden Age: Under Mansa Musa, Mali reached its zenith. His legendary pilgrimage to Mecca showcased the empire’s wealth and fostered international trade relations.

Timbuktu: This city became a center of learning and commerce, attracting scholars and traders from across the Islamic world.

Songhai Empire

Expansion: Songhai controlled major trade routes, becoming one of the largest empires in African history.

Economic Growth: Gao, the capital, flourished as a trade and cultural center.

Military Dominance: The empire’s strong military ensured the security of trade routes.

Effects of the Trans-Saharan Trade

The Trans-Saharan trade routes had far-reaching effects on Africa and the world:

Economic Prosperity

Wealth Accumulation: Trade enriched West African kingdoms, funding architectural projects, education, and governance.

Global Integration: Africa became an integral part of the global economy, exchanging goods and ideas with Europe and Asia.

Cultural Enrichment

Religious Transformation: Islam became deeply rooted in West African societies, influencing governance, education, and culture.

Art and Architecture: Trade facilitated the exchange of artistic techniques, leading to the construction of iconic structures like mosques and palaces.

Political Developments

Rise of Empires: Wealth from trade enabled the growth of centralized states and empires.

Diplomatic Relations: African rulers established connections with foreign powers, fostering alliances and mutual respect.

Mansa Musa: The Wealthiest King of Mali

Mansa Musa, the 14th-century ruler of the Mali Empire, is often regarded as the richest man in history. His reign highlighted the prosperity of the Trans-Saharan trade:

Pilgrimage to Mecca: Mansa Musa’s lavish journey brought global attention to Mali. His distribution of gold along the way caused inflation in several regions, showcasing the empire’s immense wealth.

Cultural Patronage: He funded the construction of mosques, libraries, and schools, promoting Islam and education in West Africa.

Legacy: Mansa Musa’s reign is remembered as a golden age of wealth, culture, and innovation.

Conclusion

The Trans-Saharan trade routes were a vital lifeline for Africa, connecting it to the rest of the world and facilitating economic, cultural, and political transformation. From the rise of powerful empires to the spread of Islam and the enrichment of global trade networks, these routes left an enduring legacy. Understanding the Trans-Saharan trade allows us to appreciate the ingenuity and resilience of the people who navigated and thrived in one of the world’s most challenging environments.

FAQs on “Trans-Saharan Trade Routes” with Detailed Answers

1. What were the Trans-Saharan trade routes?

The Trans-Saharan trade routes were a network of trade routes across the Sahara Desert that connected North Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of the Mediterranean world. These routes facilitated the exchange of goods, culture, and ideas for centuries.

2. Why were the Trans-Saharan trade routes important?

These routes were crucial for the economic, cultural, and political development of the regions they connected. They enabled the trade of gold, salt, ivory, and slaves, and facilitated the spread of Islam, knowledge, and technologies.

3. When did the Trans-Saharan trade routes flourish?

The trade routes flourished from the 8th century to the 16th century, peaking during the medieval period when Islamic empires and kingdoms like Mali and Songhai dominated the region.

4. What goods were traded on the Trans-Saharan routes?

Goods included:

From Sub-Saharan Africa: Gold, ivory, slaves, and kola nuts.

From North Africa: Salt, textiles, horses, and manufactured goods.

From the Mediterranean: Glassware, books, and luxury items.

5. What role did gold play in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Gold was one of the most significant commodities, primarily sourced from West African kingdoms like Ghana, Mali, and Songhai. It was traded for salt and luxury goods, fueling economies in Africa and Europe.

6. Why was salt so valuable in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Salt was a vital commodity for preserving food and maintaining health. It was mined in the Sahara, particularly in places like Taghaza and Taoudenni, and traded to Sub-Saharan Africa, where it was scarce.

7. What role did Islam play in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Islam provided a unifying cultural and religious framework for trade. Muslim merchants facilitated trade, and Islamic law (Sharia) governed commercial transactions, ensuring trust and fairness.

8. What were the key trading centers in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Major trading centers included:

Timbuktu (Mali)

Gao (Mali)

Agadez (Niger)

Ghadames (Libya)

Sijilmasa (Morocco)

9. Who were the main traders on the Trans-Saharan routes?

The main traders were Berbers, Tuaregs, and Arab merchants, who acted as intermediaries between Sub-Saharan Africa and North Africa.

10. What role did camels play in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Camels, known as the “ships of the desert,” were essential for crossing the harsh Sahara. They could carry heavy loads, travel long distances without water, and withstand extreme temperatures.

11. What were the challenges of traveling the Trans-Saharan trade routes?

Challenges included:

Harsh desert conditions (heat, sandstorms).

Limited access to water.

Threats from bandits and raiders.

12. How did the Trans-Saharan trade routes impact West African empires?

The trade routes enriched West African empires like Ghana, Mali, and Songhai by providing access to wealth and resources, enabling them to build powerful armies and develop urban centers.

13. What was the role of Timbuktu in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Timbuktu was a key trading hub and a center of Islamic learning. It attracted scholars, merchants, and goods, making it a symbol of wealth and culture.

14. How did the Trans-Saharan trade routes influence culture?

The trade routes facilitated cultural exchange, spreading Islam, Arabic language, art, and architecture across Africa. They also encouraged the blending of local traditions with external influences.

15. What were the environmental impacts of the Trans-Saharan trade?

Increased activity led to the development of oases and deforestation in regions used for caravan fuel. Overgrazing by camels also contributed to soil degradation.

16. How did the Trans-Saharan trade routes influence technology?

The trade encouraged advancements in navigation, camel saddles, and the construction of oases, which supported long-distance desert travel.

17. What role did women play in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Women participated in production (e.g., weaving textiles) and sometimes managed local markets. Enslaved women were also traded and employed in households or as concubines.

18. What were the political impacts of the Trans-Saharan trade?

The wealth generated from trade strengthened kingdoms and empires, enabling them to expand their territories and establish centralized governance.

19. How did the Trans-Saharan trade routes influence religion?

The routes facilitated the spread of Islam, which became the dominant religion in many parts of West Africa, shaping governance, education, and culture.

20. What was the role of Ghana in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Ghana was an early West African empire that controlled trade routes and taxed goods like gold and salt, accumulating immense wealth and influence.

21. How did Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage highlight the Trans-Saharan trade?

Mansa Musa, the ruler of Mali, showcased the wealth generated by the trade during his pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324, distributing gold and gaining global recognition.

22. What is the legacy of the Trans-Saharan trade?

The trade left a lasting impact on African economies, urbanization, and cultural exchanges, contributing to the historical richness of the region.

23. What was the role of Sijilmasa in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Sijilmasa was a key northern terminus of the trade routes, where goods from Sub-Saharan Africa were exchanged for Mediterranean and North African products.

24. What goods did the Mediterranean contribute to the Trans-Saharan trade?

The Mediterranean supplied luxury goods, weapons, textiles, and books, enriching the African societies involved in the trade.

25. How did the Trans-Saharan trade routes decline?

The routes declined due to the rise of Atlantic trade in the 15th century, European colonization, and the shift in global economic centers.

26. What role did the Tuareg play in the Trans-Saharan trade?

The Tuareg were skilled desert navigators and caravan leaders who transported goods across the Sahara, ensuring the trade’s success.

27. How did the Trans-Saharan trade routes influence education?

Trade brought books and scholars to cities like Timbuktu, leading to the establishment of renowned centers of learning, such as the Sankore University.

28. What was the role of Gao in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Gao was an important trading and administrative center for the Songhai Empire, serving as a hub for gold, salt, and cultural exchanges.

29. What were the main caravan routes in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Key routes included:

Western route (Timbuktu to Sijilmasa)

Central route (Gao to Tripoli)

Eastern route (Lake Chad to Cairo)

30. What was the role of Berbers in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Berbers controlled much of the trade, acting as intermediaries, guides, and traders, facilitating the flow of goods across the Sahara.

31. How did the Trans-Saharan trade routes shape African urbanization?

The trade routes fostered the growth of cities like Timbuktu, Gao, and Agadez, which became vibrant economic and cultural centers.

32. What was the role of slaves in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Slaves were a significant commodity, often captured in wars and transported to North Africa and the Mediterranean for domestic or agricultural labor.

33. How did the Trans-Saharan trade influence language?

Arabic became a lingua franca along the trade routes, facilitating communication and the spread of Islamic education.

34. What was the significance of kola nuts in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Kola nuts, valued for their stimulant properties, were a prized commodity in North Africa and the Middle East, sourced from West Africa.

35. What role did oases play in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Oases provided essential water and resting points for caravans, supporting trade and settlements in the desert.

36. How did geography influence the Trans-Saharan trade?

The Sahara’s vastness necessitated the use of specific routes, dictated by oases and terrain, making navigation and planning critical.

37. What is the historical significance of the Songhai Empire in the Trans-Saharan trade?

The Songhai Empire controlled key trade routes, amassing wealth and power, and fostering cultural and educational advancements.

38. How did European exploration impact the Trans-Saharan trade?

European exploration and the establishment of Atlantic trade routes shifted the focus of trade, reducing the importance of the Trans-Saharan routes.

39. What role did taxation play in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Empires like Ghana and Mali taxed goods passing through their territories, generating significant revenue and strengthening their economies.

40. How did the Trans-Saharan trade influence art?

Artistic traditions were enriched through the exchange of materials, techniques, and motifs, blending African and Islamic influences.

41. What was the role of Agadez in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Agadez was a key caravan stop and trading hub, linking central routes to North African markets.

42. How did gold mining support the Trans-Saharan trade?

Gold mines in West Africa provided a steady supply of the metal, fueling trade and making the region a major economic powerhouse.

43. What were the social impacts of the Trans-Saharan trade?

The trade influenced social hierarchies, with merchants and scholars gaining prominence and slavery becoming a significant institution.

44. How did the Trans-Saharan trade influence governance?

Wealth from trade enabled rulers to consolidate power, build armies, and maintain infrastructure, fostering centralized states.

45. What role did architecture play in the Trans-Saharan trade?

Islamic architectural styles influenced the design of mosques, palaces, and public buildings in trade cities.

46. How did the Trans-Saharan trade routes impact food?

The exchange introduced new crops, such as wheat and dates, to Sub-Saharan Africa, diversifying diets and agriculture.

47. What was the impact of the Almoravid dynasty on the Trans-Saharan trade?

The Almoravids controlled key trade routes and promoted Islamic law, influencing the trade’s organization and cultural framework.

48. How did trade routes connect to global networks?

The Trans-Saharan routes linked Africa to Mediterranean and Middle Eastern trade networks, which further connected to Asia and Europe.

49. What is the modern relevance of the Trans-Saharan trade routes?

The legacy of the routes is visible in cultural and economic practices, while modern infrastructure projects aim to revive parts of these historic networks.

50. What lessons can we learn from the Trans-Saharan trade?

The trade highlights the importance of cooperation, resource management, and the role of cultural exchange in building interconnected societies.