Table of Contents

Toggle9.1 Definition of a Circuit

As of 2021, the College Board tests only Units 1-7 on the AP Physics 1 exam. While this page’s content will not be directly tested, it remains a valuable resource for understanding circuits and their fundamental concepts.

Enduring Understanding 1.B ⚡

Electric charge is a property of an object or a system that affects its interactions with other objects or systems containing the charge.

Essential Knowledge 1.B.1

Electric charge is conserved. The net charge of a system is equal to the sum of the charges of all objects within the system.

What is a Circuit?

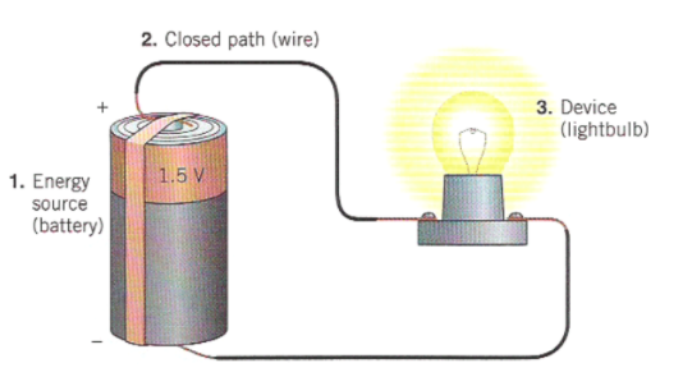

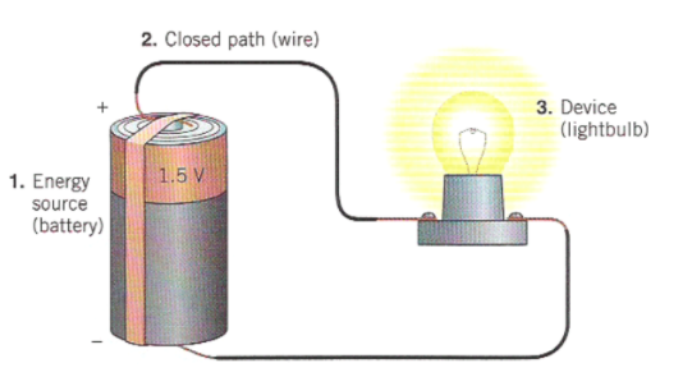

A circuit is a closed loop through which electrical current flows. If the loop is open or obstructed, the current cannot return to its starting point, and electricity ceases to flow. Any devices connected in such an interrupted loop will not function. Common ways of breaking a circuit include using switches or removing/blowing out light bulbs.

Types of Circuits

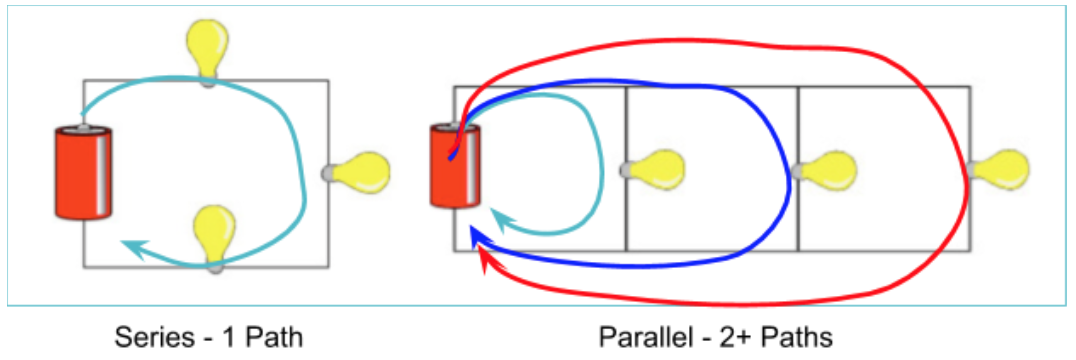

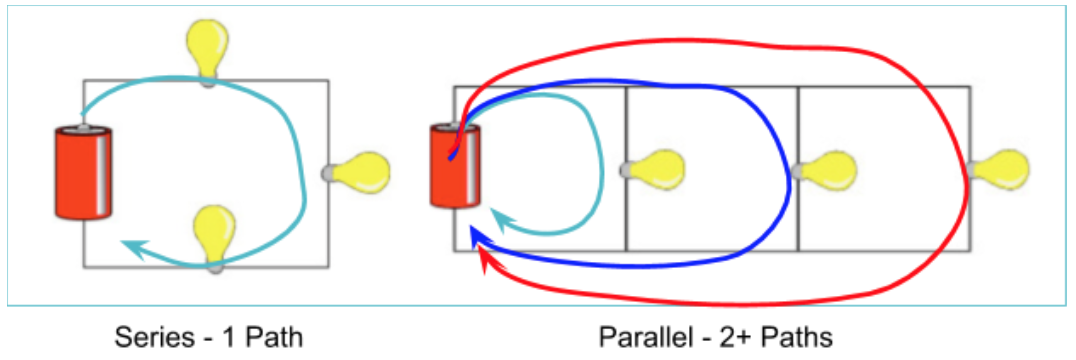

Series Circuit

Contains a single path for current to flow. All components are connected sequentially, so the same current travels through each component.

Parallel Circuit

Offers two or more paths for the current. The current divides among the available paths, allowing components to operate independently.

Electrical Current (I)

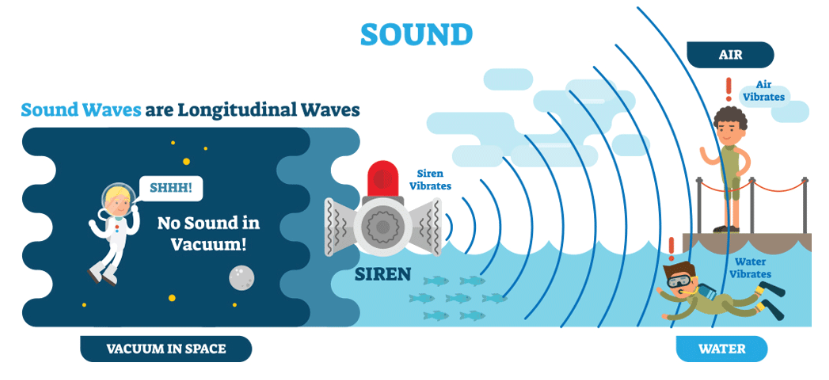

Current is the flow of electric charge through a conductor. It is comparable to the flow of water in a pipe. The greater the volume of water passing through a point per second, the higher the water flow. Similarly, the more charge passing through a conductor per second, the greater the current.

Formula:

Where:

I = Current (Amperes, A)

q = Charge (Coulombs, C)

t = Time (Seconds, s)

Key Point:

Electric charge is conserved. This principle, introduced in Unit 8, means the total charge in a circuit remains constant. Charge cannot be “used up” in a circuit.

Other Key Circuit Terms 🔍

Voltage

Voltage represents the energy each charge carrier receives as it moves through the circuit. Batteries typically provide the voltage for circuits. As charges move through the circuit, they transfer energy to devices such as light bulbs or motors, causing a voltage drop along the way. This concept will be crucial for circuit analysis.

Resistance

Resistance is the opposition to electrical current. It depends on the properties of the conductor. Using the water analogy, resistance is akin to a kink in a hose, reducing water flow. In circuits, resistors are added to control the current and are often responsible for converting electrical energy into heat.

Ohm’s Law:

Where:

V = Voltage (Volts, V)

I = Current (Amperes, A)

R = Resistance (Ohms, Ω)

Power

Electric Power refers to the rate at which electrical energy is consumed in a circuit. Using Ohm’s Law, the power equation can be adapted based on available terms (voltage, current, resistance):

Power Formula:

Where:

P = Power (Watts, W)

I = Current (Amperes, A)

V = Voltage (Volts, V)

You can rewrite this using Ohm’s Law as:

Why Understanding Circuits Matters

Mastering the concepts of circuits not only builds foundational physics knowledge but also equips you to solve real-world problems, from designing electrical systems to troubleshooting household electronics. Explore the next section to dive deeper into resistance and its applications.

Recent Posts

- The Periodic Table

- PAST PAPERS

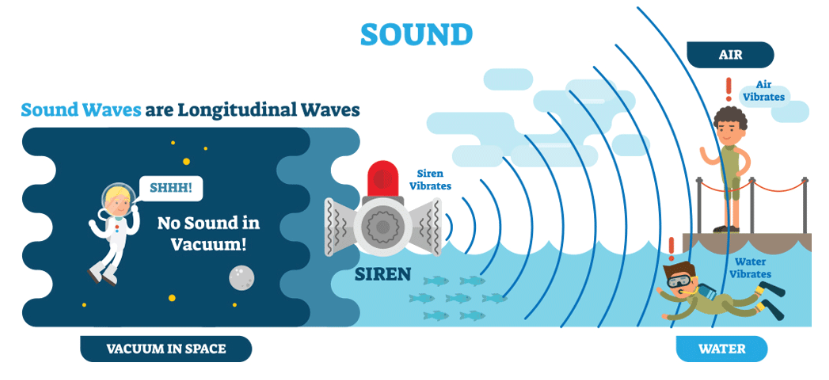

- Unit 10 Overview: Mechanical Waves and Sound

- 9.4 Kirchhoff’s Junction Rule and Ohm’s Law (Resistors in Series and Parallel)

- 9.3 Ohm’s Law and Kirchhoff’s Loop Rule (Resistors in Series and Parallel)

- 9.2 Resistivity

- 9.1 Definition of a Circuit

- Top Public Universities in America

- Best Liberal Arts Colleges in America

- Top 25 Community Colleges in America

- University of Chicago

- Claremont McKenna College

- University of Michigan – Ann Arbor

- Johns Hopkins University

- Cornell University

Choose Topic

- ACT (15)

- AP (20)

- AP Art and Design (5)

- AP Physics 1 (1)

- AQA (5)

- Banking and Finance (1)

- Biology (13)

- Business Ideas (68)

- Calculator (67)

- Chemistry (3)

- Colleges Rankings (30)

- Computer Science (4)

- Conversion Tools (135)

- Cosmetic Procedures (50)

- Cryptocurrency (49)

- Edexcel (4)

- English (1)

- Environmental Science (2)

- Exam Updates (1)

- Finance (17)

- Fitness & Wellness (164)

- Free Learning Resources (187)

- GCSE (1)

- Health (107)

- History and Social Sciences (20)

- IB (1)

- IGCSE (2)

- Image Converters (3)

- IMF (10)

- Math (39)

- Mental Health (58)

- OCR (3)

- Past Papers (463)

- Physics (5)

- SAT (36)

- Sciences (1)

- Short Notes (5)

- Study Guides (26)

- Syllabus (19)

- Tutoring (1)

Recent Comments

9.4 Kirchhoff’s Junction Rule and Ohm’s Law (Resistors in Series and Parallel)

9.3 Ohm’s Law and Kirchhoff’s Loop Rule (Resistors in Series and Parallel)

Unit 10 Overview: Mechanical Waves and Sound

9.4 Kirchhoff’s Junction Rule and Ohm’s Law (Resistors in Series and Parallel)